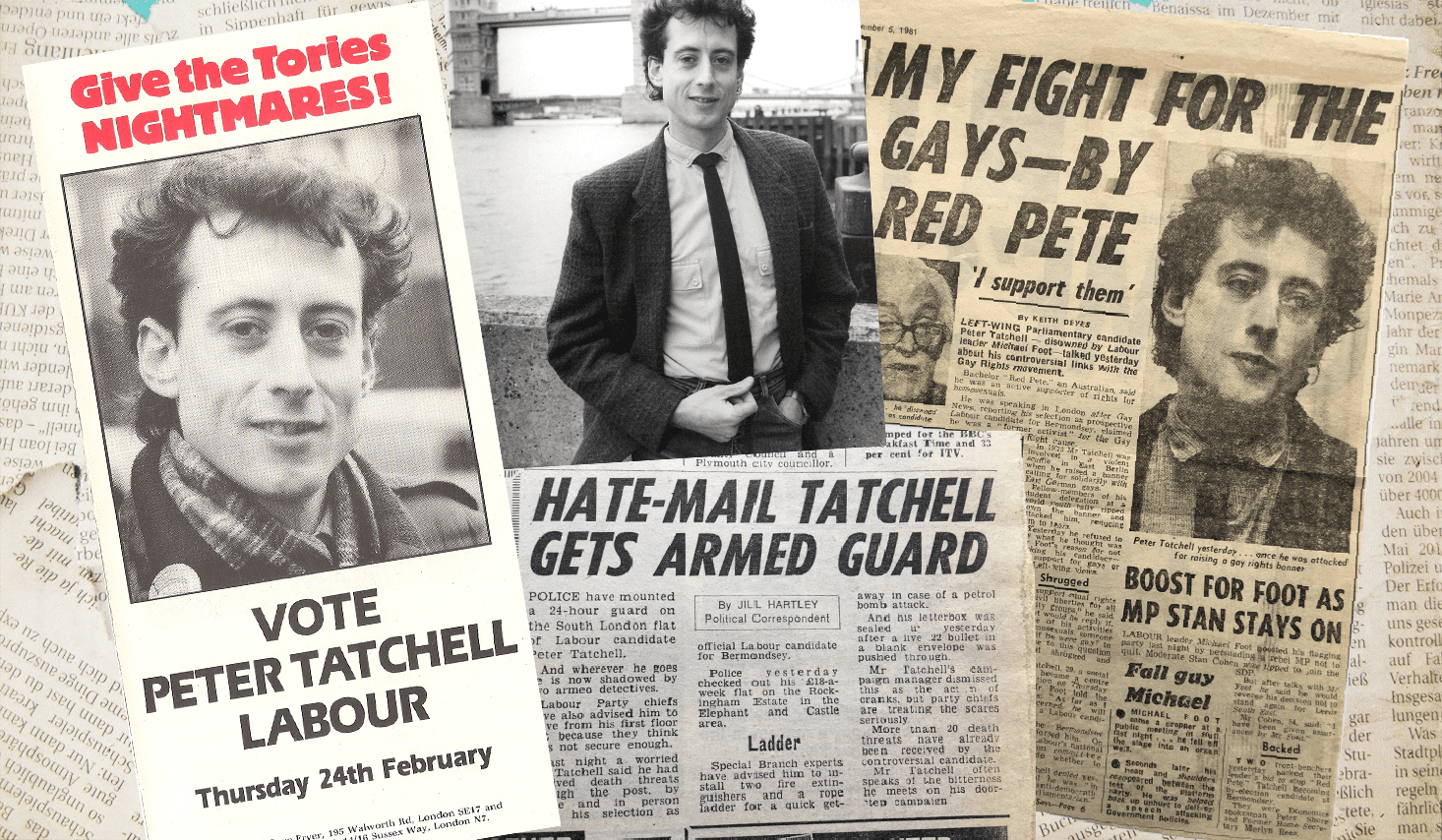

“Some commentators said it was the most sustained vilification of a gay public figure since Oscar Wilde,” says Peter Tatchell as he recalls what it was like to run in the 1983 Bermondsey by-election, which has since been described as the most dirty, violent and homophobic to take place in the UK. Already known as a prominent human rights activist, Tatchell sought to become the London constituency’s next Labour MP when Bob Mellish resigned – though nothing could have prepared him for the “vicious campaign” that followed. In the run up to the vote, he was subjected to more than 100 assaults, 30 attacks on his flat and even a bullet being put through his letterbox – as well as countless death threats and hateful messages. “So that gives you a flavour of the scandalous, outrageous nature of that by-election, which was for me, as a 31-year-old, a real baptism of fire,” he tells GAY TIMES ahead of its 40th anniversary on 24 February 2023.

Assaults on him ranged from verbal abuse to having bricks and bottles thrown at his home, in addition to multiple arson attempts against him and people trying to run him down with their car on more than one occasion. Despite this, he explains that the “police refused point blank” to give him official protection. “The best they gave me was, occasionally at night, they sent a couple of officers to walk past my flat once or twice,” he continues. “But, of course, the attacks on my flat happened when they weren’t there. I think, by general accounts, no other election candidate, certainly in the 20th century, ever faced such extreme violence.” Looking back on it all these years later, Tatchell still doesn’t know how he “coped and got through” this onslaught from politicians and the media at both a local and national level.

READ MORE: Peter Tatchell on the past, present and future of LGBTQ+ activism

But what was it that made Tatchell the subject of so much visceral hatred? He says that, at the time, his policies – which included LGBTQ+ equality, a national minimum wage and a peace settlement in Northern Ireland – were “deemed to be extreme” by voters, despite being the norm today. “I stood on the most radical LGBT+ rights platform of any parliamentary candidate before or indeed probably since,” he explains. “But I was also passionately concerned about social justice issues as well.” Although he initially had no intention of standing in the by-election, Tatchell struggled with watching things go “downhill in the country” as a result of Margaret Thatcher’s government, which had risen to power in 1979, and as such wanted to implement change as an MP. He continues: “It was very clear from early on that the government of Margaret Thatcher had a very moralistic family values agenda which excluded LGBT+ people. On top of that, her social policies were very damaging to ordinary people. There was a huge increase in unemployment and a huge rise in homelessness. So for all these reasons, I felt I wanted to go to Parliament to shake things up, to join with other Labour MPs to challenge the Thatcher government.”

Not a single national newspaper supported Tatchell’s candidacy and he was routinely harassed by the press, some of which would run fabricated or exaggerated claims about him, which in turn whipped up public hysteria. “From when I was selected as the Labour candidate in November 1981 to the by-election in late February 1983, I was hounded nonstop by the paparazzi,” he says. “They would stalk outside my workplace, my home, they’d follow me to the shops.” Tatchell also describes “intimidating” incidents in which photographers would put telephoto lenses through his windows, with other members of the press posing as relatives to gain information about him from neighbours. “It just pushed me on and I just went from one thing to another,” he says of how he dealt with these kinds of invasions of his privacy. “I never dwelled much on what happened. After a violent attack, I would just pause to acknowledge it and, perhaps, struggle to contain my emotions. But very quickly, I just bounced back into doing the next thing that needed to be done – to go out canvassing, to knock on more doors, to hopefully counteract, by my personal presence, the lies and smears put out by the tabloid press.”

There is also no question over the role homophobia played in Tatchell’s treatment at the time. In the 1980s, there were no openly LGBTQ+ MPs, political support for the community’s rights was virtually non-existent and homophobic rhetoric was rife in the media. Most of the tabloid press coverage about Tatchell honed in on his sexuality, while anonymous leaflets titled ‘Which queen will you vote for?’ describing him as a “traitor” to the country were circulated alongside his address and a message encouraging enraged voters to show him exactly how they felt. “All throughout the constituency in gigantic three-foot-high block lettering in white paint were slogans like, ‘Tatchell is a communist poof’, ‘Tatchell is queer’, ‘Tatchell is an n-lover’ – a racist appeal to voters because of my support for the Black community,” he remembers. Tatchell says that he was “always on edge” because of the smear campaign, which caused him to suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and night terrors. “I would relive some of these attacks and jump bolt upright in my bed with my heart pounding so strongly that I feared it was going to burst out of my chest,” he shares. “It was absolutely terrifying.”

Four decades later, Bermondsey still holds the record for being the largest by-election swing in British political history. Simon Hughes of the Liberal Party emerged victorious with 17,017 votes, while Tatchell finished second with just 7,698. Despite the loss, he says he’s still “glad” he ran for office, though notes that his election could have helped advance certain legislation more quickly. “I think I could have, with other members of parliament, made a difference,” Tatchell adds. “There are so many issues that I wanted and planned to raise, and I think, maybe, that I could have helped perhaps push forward things like the Equality Act much sooner than in 2010.” He continues: “It’s extraordinary that in 1983, in the by-election, I was advocating a broad based, comprehensive Equality Act to protect everyone that was widely denounced as extremist. It took until 2010 for that legislation to be enshrined in the Equality Act. If I’d been elected in 1983, I would have pushed and hopefully been able to get that statute on the books much, much sooner.”

READ MORE: What challenges will LGBTQ+ people around the world face in 2023?

Things like the so-called ‘trans debate’ and the government’s failure to ban ‘conversion therapy’ for all years after initially promising to do so show that anti-LGBTQ+ rhetoric still exists in politics today, which Tatchell acknowledges. “There is still plenty of prejudice, no doubt about it, and politics is often quite toxic,” he says. “But to be frank, it’s nothing on the scale of what I went through 40 years ago. You know, the Batley and Spen by-election was pretty bad, but even that was minor by significance in comparison to what I went through. It is hard to imagine today just how bad it was.” He does, however, believe that “one of the really positive things” to come out of the Bermondsey by-election was that it “made it easier for subsequent LGBT+ candidates” to run for office. “After it was all over, when people realised the horrendous abuse that I’d suffered, it provoked widespread revulsion, not just among the public, but even among many of the journalists who had been party to it,” Tatchell states. “And this meant that when subsequent gay candidates stood or came out, like Chris Smith, who declared his sexuality a year later in 1984, they did not suffer the abuse and vilification that I did.”

Since losing the by-election in 1983, Tatchell has become a name synonymous with LGBTQ+ activism in the UK and he has “been able to contribute to many of the changes that our community has won” in the 40 years since then. “The extreme vicious homophobia of the Bermondsey by-election reminded me and the whole community of the scale of prejudice that still existed and that prompted me to reignite my previous campaigning work on LGBT+ issues,” he says, adding: “I think that having not been elected has given me the freedom and flexibility to say exactly what I feel, to campaign passionately for the issues I care about in a way that wouldn’t have been possible on the same scale if I’d been elected an MP.” With LGBTQ+ representation in politics reaching record highs across the UK in recent years, there’s no denying that things have come a long way since that fateful by-election. In the next four decades, Tatchell wants to see this go even further given that the community still has “battles to fight and win”. He continues: “I would love to see an openly lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender Prime Minister and Archbishop of Canterbury. I would also love to see us achieve a situation where no one cared about anyone’s sexual orientation or gender identity, where all we cared about was love and respect for each other.”

Hating Peter Tatchell, the documentary which follows Peter Tatchell from his early life to his fight for justice amid controversy and political turmoil, is streaming now on Netflix.