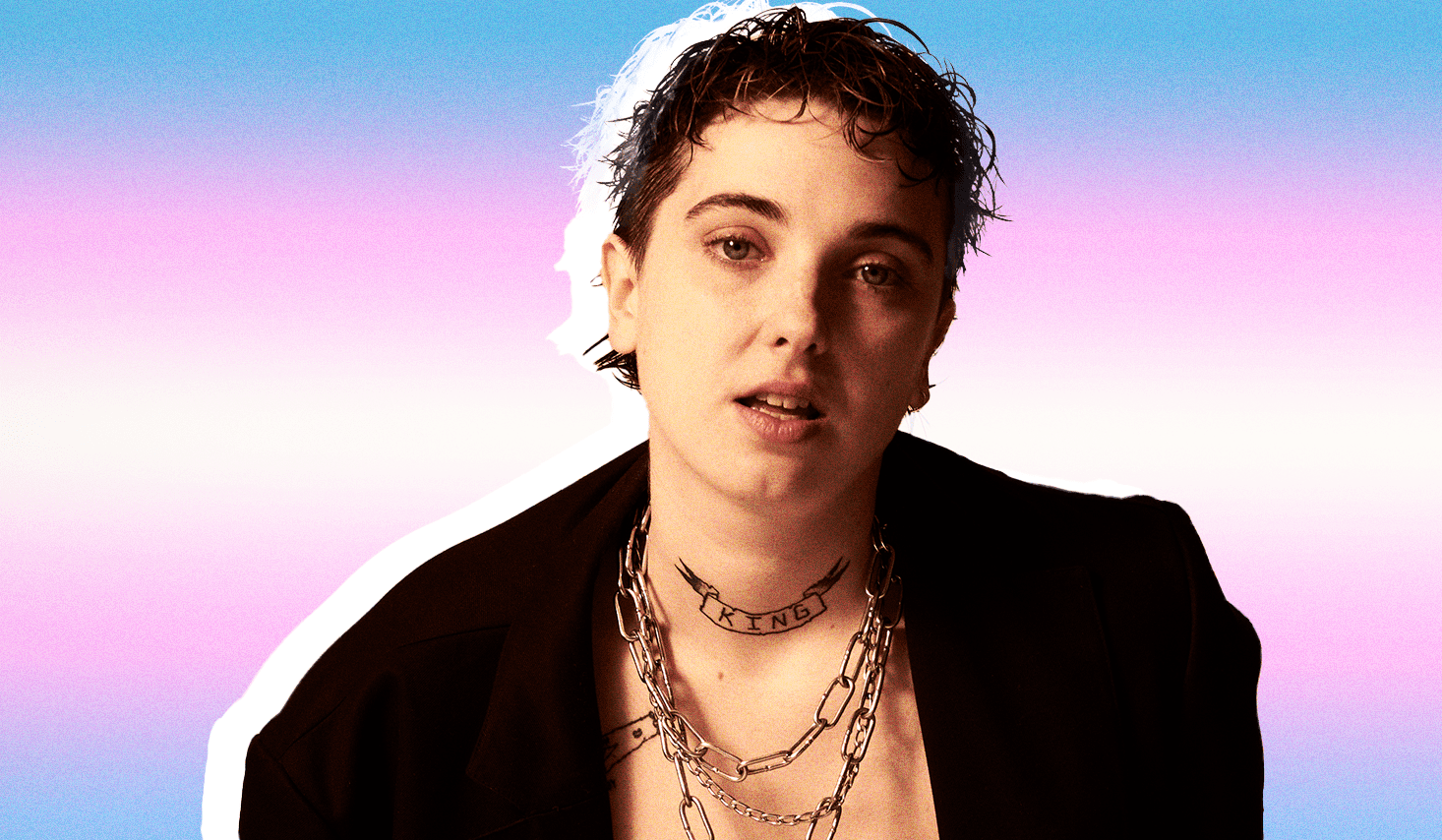

Foreheads touching with a gentle intimacy, queer love radiated from the image of transmasculine non-binary musician Campbell King and genderqueer creative Mia Maxwell, featured as part of Burberry’s Valentine’s Day campaign B:MINE. Their complementary mullets framed softly resting faces, with Campbell’s neck and chest tattoos tracing down to their visible top surgery scars. This moment – shared on Burberry’s Instagram page on 25 January – captured the celebration of love between two visibly genderqueer individuals, representing just one example of a diverse human experience.

What began as a powerful campaign soon turned sour, leaving Campbell and Mia feeling “violated” and disempowered. Thousands of hate comments quickly gathered under the post, with many expressing outright disgust. Some stated that this photo had “nothing to do with fashion” and questioned whether Burberry was “close to bankruptcy”, while others compared Campbell’s top surgery scars with “self-mutilation”. In the following days, discussion appeared on forum threads on Mumsnet and on sites such as the Daily Mail – with columnist Sarah Vine comparing the trans experience to “eating disorders or mental health issues”. The campaign was even discussed on the conservative talk show, The Megyn Kelly Show – Kelly has a history of inflammatory language – where guests described the Valentine’s moment as “over-the-top” and “provocative”.

Then, in the early hours of 27 January, Burberry quietly deleted the post without any accompanying response or formal statement. According to Campbell and Mia, the brand also acted thus without communication with the models, and in direct opposition to their wishes as expressed in an email to Burberry from Campbell’s management.

“We were quite clear on what we wanted,” Campbell tells GAY TIMES. “We didn’t want the post to be removed because it’d be giving the impression to all the people who have directed hate that they’ve won. We wanted them to moderate the comments and to issue [a statement in] support for the trans community [or], at the very least, support for the models.”

The backlash, which notably misgendered Campbell, claimed to be speaking out of concern for easily impressionable “young girls” who could be influenced by the “glamourisation” of a double mastectomy. This procedure aims to remove breast tissue commonly as cancer treatment, but also as a form of gender-affirming healthcare for transmasculine people. However, the deep-seated transphobia was apparent and dripping in the putrid scent of hypocrisy. Would such “feminist” critics – who claim to champion brands that feature “real women” – still maintain the campaign was “glamorising” double mastectomy if it featured a woman with scars from a cancer procedure? Would they still state that the woman was being “exploited, not celebrated”?

Trans people are not wounded, traumatised, or unwell due to our identities – there is endless joy in the trans existence. The marginalisation and violence we face is instead a symptom of society’s attitudes and behaviours towards us, stemming from a lack of education – LGBTQ+ inclusive education has only been mandatory in schools in England since September 2021, much later than in Scotland and Wales –, and the normalisation of vitriol in the political and media landscapes. It is upheld by those very individuals who would question the authenticity of a genderqueer couple’s intimacy and compare trans representation with the “heroin chic” trend.

“Our life is so full of joy and our queerness is so full of joy,” says Campbell. “I don’t associate queerness with bleak stuff. Our queerness is brilliant and happy and my surgery was euphoric. It was one of the highlights of my life – one of the things that have made me feel happier than I’ve ever felt.”

Our queerness is brilliant and happy and my surgery was euphoric. It was one of the highlights of my life

Yet, in response to Burberry’s campaign, individuals labelled Campbell and Mia as unhappy and vulnerable. Across the internet, emotional reactions of discomfort overshadowed basic respect for another human being – a rejection of the unknown rooted in fear. Multiple comments, articles, and Kelly’s talk show also drew comparisons with Balenciaga’s recent campaign, which garnered criticism for featuring children with teddy bears wearing bondage gear and an image of a Supreme Court opinion on a child pornography case. When the far-right has long labelled queer and trans people as “groomers”, such harmful claims against the trans community are not so innocent.

Campbell feels that, whether that was their intention or not, Burberry’s choice to remove the post and not release a statement is “leaving space for anti-trans rhetoric to go unchallenged”. When asked for comment, a Burberry spokesperson told GAY TIMES: “We have a longstanding commitment to supporting the LGBTQ+ communities, working with a number of external partners, and we believe it is important to celebrate diversity in our campaigns and shows. This will continue.”

Whatever Burberry’s intention or future plans, the reality is that these recent events did not take place in a vacuum. Trans people have a history of experiencing inequality – from unique struggles with their mental health to difficulty accessing safe and inclusive housing support services. Just in the last four years, anti-trans hate crime in the UK has risen by 156%. This harrowing reality has even led some to highlight the murders of trans people, especially women of colour, as an ‘epidemic’. Most recently, thousands gathered across the UK to mourn the murder of 16-year-old trans girl Brianna Ghey, who was stabbed to death in Cheshire on 11 February following years of bullying.

Within this context, silence is complicity. As trans activist Sophie Gwen Williams said in her speech at Trans Pride 2020: “You cannot continue to consume our excellence and our talent, and then ignore us when we’re being treated violently the next fucking day.” Trans people’s lives are not up for debate – yet many continue to treat them as such. Within this socio-political climate, brands cannot simply use the trans community’s creativity to appear inclusive. Without further support, this perceived representation can lean far too readily into pinkwashing and a ruthless cash grab.

Visibility must always be closely followed by a provision of safety

While trans people continue to be some of the most marginalised in society, companies must be prepared for the backlash and be willing to reaffirm their commitment to uplifting LGBTQ+ voices. “To shine a light on queer and trans people without additional and specialised protection is simply leaving some of the most marginalised people in society to stand alone in a dangerously vulnerable position,” says Cora Hamilton, co-founder and creative director of LGBTQIA+ talent agency uns*. “Visibility must always be closely followed by a provision of safety. When a brand is putting out imagery featuring trans+ people, there must be a framework of protection in place in preparation for a negative response.”

Simple steps can be taken to ensure that trans talent feel empowered and safe – the approach simply must be rooted in care. Behind the scenes, this can look like ensuring everyone on set uses correct pronouns and discussing clothing options with individuals to avoid triggering their gender dysphoria. It can also be wise to discuss safeguarding concerns in advance with leadership teams to prepare internally for any backlash.

Maxine Heron, marketing manager at gender-free makeup brand Jecca Blac, highlights the need for consistent open communication and for vigilance “with every step of releasing content into the public eye”. “It’s about making sure that everyone’s well-being is being prioritised through good communication about anything that the people in the video are not comfortable with, on the day of shooting and then afterwards as well,” she adds.

So, what do we, as queer people, do when organisations fail to fulfil their duty of care? Campaigning methods such as open letters and boycotts can be impactful in certain contexts. Recently, New York Times’ harmful coverage of trans people prompted thousands of contributors, subscribers, and readers to sign a powerful, coordinated letter to demand better from the publication. In fact, last year, trans journalists Vic Parsons and Freddy McConnell even pulled out of the Guardian’s Pride special coverage, writing in a letter that they will “no longer write for The Guardian until it changes its trans-hostile and exclusionary stance.”

It’s about making sure that everyone’s well-being is being prioritised through good communication

However, when confronting profit-driven brands with a sales target to prioritise, such movements need support and championship from within. “Throwing fire at an established global corporation from the outside is almost never going to work,” says Cora.“Unless their reputation is threatened, a large brand will rely only on sales to measure their success and, for the most part, positive change is a long game and occurs from within.”

The decision to boycott can also have negative repercussions on LGBTQ+ visibility, especially when accountability from profit-driven brands is not guaranteed. Representation is crucial and not to be discarded lightly. It helps LGBTQ+ young people and others who may be exploring their identities to feel less alone, and aids community-building. Representation also exposes us to the diversity of humanity and fosters a more accepting society. Perhaps if LGBTQ+ people had been more widely represented in mainstream media and campaigns over the last 50 years – if Thatcher’s homophobic law Section 28 had not been in place in the UK until only 2003 – the response to Burberry’s campaign may have been one of widespread acceptance.

In order to create such a future, organisations must not only stand by their decisions, even if deemed “provocative” by conservative commentators, but also offer marginalised individuals a seat at the table. “If a diverse cast of models is the only step a brand is making towards diversity then we are inching towards a better future in fashion at a snail’s pace. We need people who have the ambition to create a better place for everyone at every level of every establishment,” Cora adds.

With inequality baked into the system, those with privilege must be willing to pass the mic and trust communities to make decisions for their own well-being. For example, Edward Enniful – British Vogue’s first Black Editor-in-Chief – has revamped the iconic fashion magazine and brought Black creatives and political advocates to the forefront. Similarly, LGBTQ+ people in positions of power also must acknowledge the responsibility to pull others up, and not shut the door at the first sign of conventional success.

“There’s a lot of exclusion and a lot of gatekeeping,” shares Campbell. “Visibility is great but, for me, the most important thing is getting indoors where you previously wouldn’t have been allowed, knocking down those barriers, and then bringing everyone in with you.” It is not enough merely to hire visibly trans individuals as the faces of fashion campaigns and media content. Brands must do more for true trans inclusion – to provide safe spaces that aid societal progress, and encourage celebration, joy, and authentic genderqueer expression.