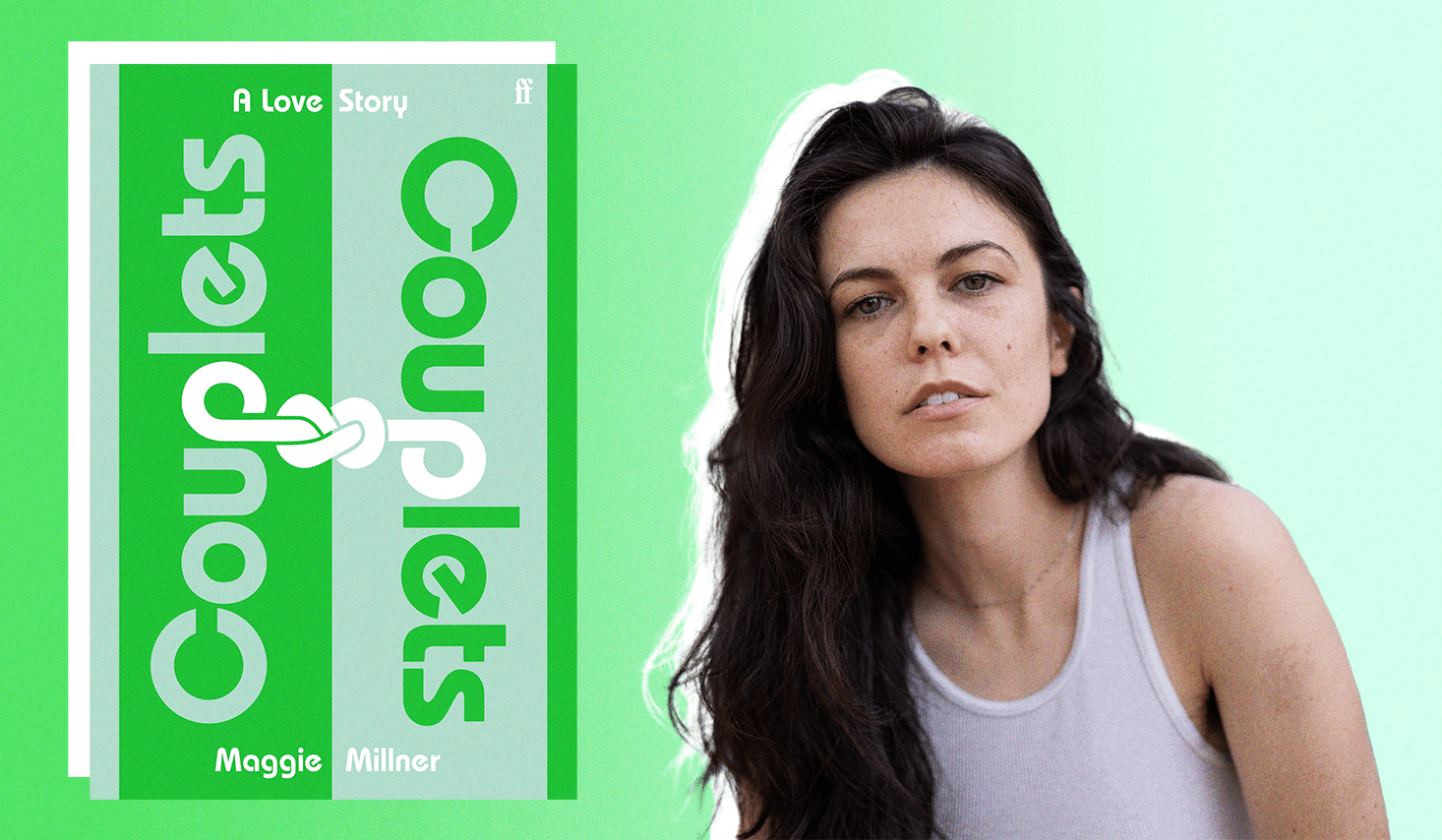

It’s slick, quick-witted, and seamlessly written. Whether she’s untangling relationships or examining queerness, Millner manoeuvres between prose and poetry in a measured yet exacting exploration of self-hood which permeates her debut novel, ‘Couplets’.

Adopting a unique hybrid mesh of verse and prose, ‘Couplets’ delves into the experience of a woman in her late twenties, who breaks from her conventional lifestyle and relationship with a man, as she finds fluidity through her engagement with queerness, polyamory and kink.

With ‘Couplets’ hitting shelves in the UK, we caught up with Millner to chat about the novel’s unique form, the boundaries of identity and what self-discovery, through language, looks like.

Hey Maggie! You’ve been on a book tour. How has that been for you?

I’ve been doing events over the past couple of weeks on the east coast and in Seattle, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. It’s been really fun. It makes everything so much less abstract, to just be actually in a room with a bunch of people and to be reading the book out loud, so it’s been really fun.

Would you say it’s been pretty cathartic to translate that in a verbal capacity?

It’s been really demanding showing up. I put a lot of pressure on myself to really show up and really perform and be really present and emotionally available during the reading, because it is a book that has a certain amount of emotional availability built into it. It has also been demanding to go fully into the emotional space that the book occupies but I think there has been catharsis in that.

Do you remember when you decided to switch from poetry to prose?

I thought [‘Couplets’] was going to be a poetry collection that resembles more traditional contemporary poetry collections where the poems are thematically related but they’re not necessarily presented in any chronological narrative. It took me until I had 25 to 30 of these little lyric poems to realise that they could be presented within a larger narrative and that that might actually serve them better. Once I realised that I just started writing into the gaps, and adding new poems and taking away some poems and then adding the prose sections last.

What do you enjoy most about playing with text and narration?

That is a great question. These poems began because I found it really satisfying to write in these rhymed couplets and rhymes are not super strict: often the rhymes are slant or imperfect. Even that kind of imperfect rhyming was so satisfying and gave me such a sense of accomplishment. I was writing into a container that already existed. Writing about an experience that felt really messy into something that resembled a coherent form was immensely pleasurable for me. At the beginning, I was writing this as events were unfolding in my own life and as I was trying to make sense of my own queer identity. Then, the larger structure and [the] more novelistic story emerged later on.

Did you at any point find it quite restrictive, knowing that you had to adhere to that structure to a degree?

Surprisingly, I found it less restrictive. Once I started writing in these couplets, I was speaking in couplets, I was writing emails in couplets, it just became the way I had trained my brain into this very particular kind of syntax and this very particular logic. I was really aware, especially as the poems accumulated, of how it’s a big ask for a contemporary reader to sit down and attend to a book, an entire book in rhyming couplets without feeling excessively claustrophobic or like they were held hostage within this really repetitive or relentless kind of form, rather than engaging with a story. [It] was a tricky balance to strike but it was really important that the reader felt brought in by the form rather than distanced by it.

Writing ‘Couplets’ you bring up big moral moments and ethical dilemmas. How did you strive to approach this without the poetry coming across as didactic?

Yeah, that’s a good question. It feels almost inevitable that those kinds of questions will dominate the consciousness of the writing because those are the questions we are consumed by as contemporary subjects, but I love your point about trying to move away from didacticism, which is interesting because the language and the jargon around queer identity exists in order to make these identities legible within a dominant discourse and to advocate for things like the right to have children or the right to be by the bedside of your partner while they’re sick.

One thing I didn’t want to do as I was writing this book was to fall into using jargon. To be clear, it’s good that these exist – there are queer activists and elders who have made my life possible. But, as a poet, there’s this question of ‘Am I writing in order to make my life legible to a straight audience or to do the work of unlearning taxonomics to make way for a more capacious understanding of identity?’ Identity, especially a relationship to queerness, has fluidity and mutability built into it and those are important properties of a queer life.

What book of poetry, or piece of poetry, prompted you to engage with your queerness made you look inwards when you were younger?

Adrienne Rich was a huge poet for me. My parents bought me her poetry when I was in high school. I was writing poems all the time and they bought me several collections of Adrienne Rich and Anne Sexton, which was amazing. I don’t think they even realised how perfect that was for me at that time. It was really formative reading Adrienne Rich and reading poems like ‘21 Love Poems’.

I grew up in a very rural place. I didn’t know any queer people. It wasn’t a necessarily queer life. I didn’t have models for the kind of life I live now and those poems were some of the first places where I saw queer desire depicted in a way that I really was like ‘Oh, this is me’ in a way that it felt urgent and thoroughly destigmatised.

‘Couplets’ blends anecdotal and fictitious experiences. How did you mark the boundary between personal and professional when writing this?

This level of intimacy and is written in the first person and it’s a draw on this highly individualised experience and people assume that it’s non-fiction. That irks me because I don’t think it’s an assumption that we make about men or straight people as often as we make it about women, queer people and other marginalised groups. I tend to insist that I am an artist and this is a book in rhyming couplets. This is not unfiltered diaristic writing; this is an act of extremely intentional artifice.

It is a tricky boundary, but I do tend to, in professional settings, be pretty rigorous about insisting on the distinction between what’s happening on the page and what’s happening in the life of the writer. They know the persona and the story that I’ve told but those are the results of a lot of aesthetic decisions that I very intentionally made.

What’s your favourite queer light read and why?

Eros the Bittersweet forever! There’s also a super fun novel coming out this summer called Dykette by my friend Jenny Fran Davis that I’ve been recommending to anyone who gets a kick out of butch-femme camp dynamics.

Last of all, why should we read (or re-read) Couplets?

No one “should” do anything! Down with the tyranny of “should!” Perhaps that ethos, more than any other, is what I hope this book will deliver.

‘Couplets: A Love Story’ by Maggie Millner is out now and available to buy here.