Coming out three times, you realise that identity can be complex. I came out as a teenager as a transgender boy, and also as gay. A few years later, I also realised I’m aromantic – but did that make me asexual and what did that mean for my relationships?

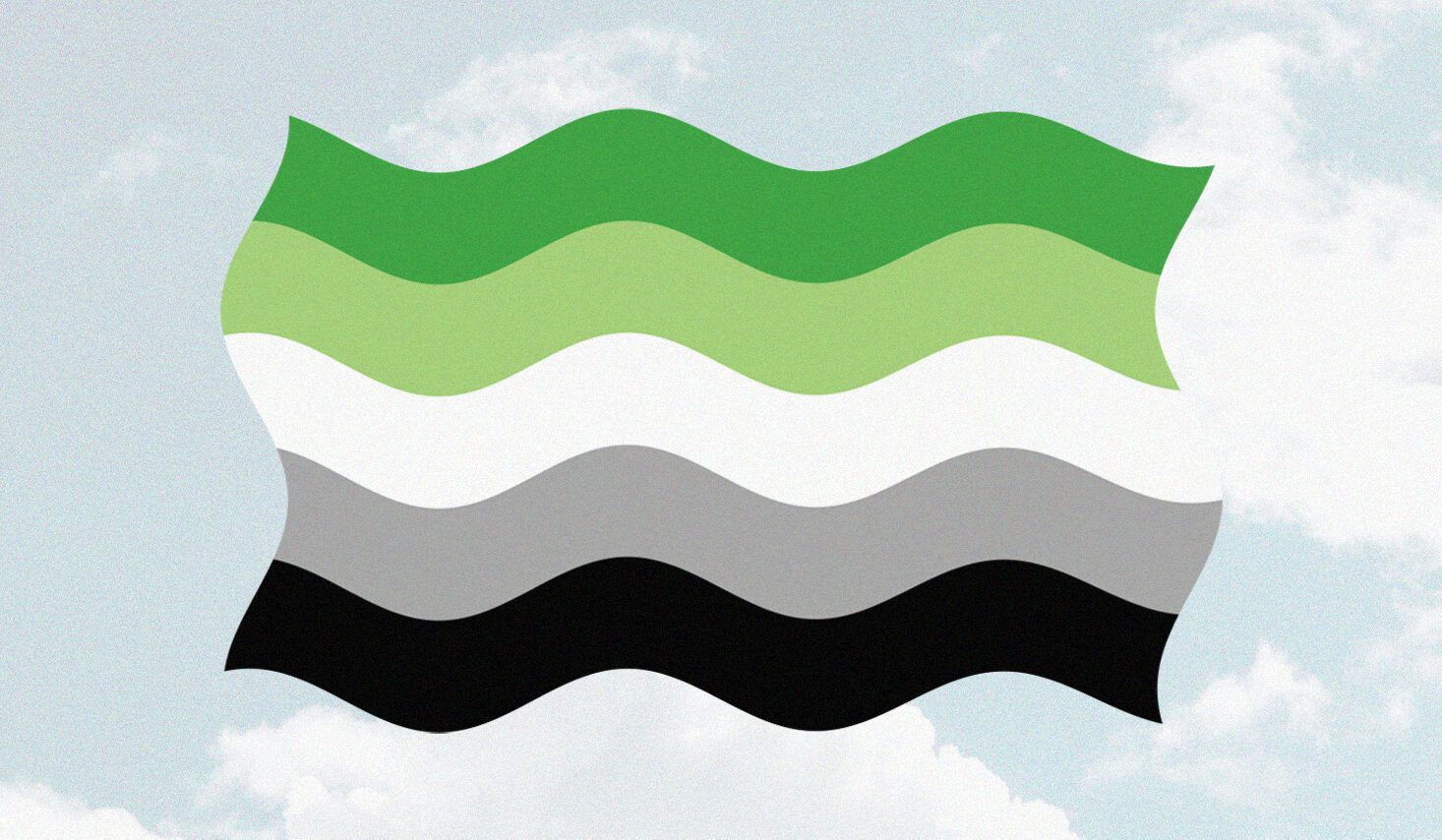

Aromantic, to me, means having little to no romantic attraction to others. Usually, it’s considered to be connected to being asexual, which means having limited or no sexual attraction towards others.

When I was younger, I developed what I thought was a crush on a good friend of mine. He was such a great guy who I just loved talking to. We had a lot in common – he was also trans and had come out at a similar time to me, so we really connected on that front.

I asked him out after a week of knowing I liked him and immediately we were very public about it. This was my first relationship after all, and I wanted to be out and proud like I’d seen my friends be with their significant others.

Surprisingly, I enjoyed the physical intimacy but I actually found myself being very much not interested in the relationship. Just one week into the relationship I called it off, citing not knowing what I really wanted, which was true. I didn’t know what I wanted out of a relationship.

The term “aromantic” had been floating around in my circle for a while. I had a good friend at school who was asexual and aromantic, but I never knew someone could be aromantic without being asexual. For a long time, I had seen those things be mutually exclusive, with aromantic awareness coming in as a footnote to asexual awareness.

Being aromantic but not asexual? I never knew it was possible but it started to make sense to me – I liked dating but I realised that I only ever really cared about physical attraction.

Then I started getting involved in more ace-spectrum circles where I was able to meet more aromantic people who shared similar or had different ideas of what being aromantic meant to them.

Some aromantic people I met said they still had romantic relationships, it’s just that their attraction was minimal. Others avoided any sort of commitment as it repulsed them.

Hearing other people talk about how they identify and use aromantic to describe their experiences helped me understand mine. I’ve realised that I don’t have to worry about others associating aromantic with asexual – aromantic is the word that fits who I am and I’m thankful that there’s the language to describe our diverse identities and the relationships we have.

But there’s still one thing I wish other people would understand: being aromantic isn’t what young people use to be trendy. It’s not a phase or a fake identity. It’s a real one that people use to describe their attractions.

It is still difficult to tell others that I am aromantic as it does quickly turn into a lesson on ace-spectrum identities. I’m okay with that though, as long as people are willing to listen and understand.

Matthias volunteers with Just Like Us, the LGBT+ young people’s charity.