These days, the queer Englishman is spoilt for choice when it comes to courting. Blessed with a plethora of specialist apps and – if he’s really old school – bars, he has instant access to community and coitus alike. Of course, it wasn’t always this way. Until 1967, buggery was a crime. Nonetheless, buggery ensued, as did the campery and antics that make Britain’s queens some of the craftiest yet. How? Polari, a forgotten cant spoken across London and the UK at large from the early-twentieth century onwards. Through it, gays could converse without outing themselves, which then came with serious reprimands: imprisonment, violence, the lot. Today, Polari’s an endangered language, and only a few fluent speakers endure.

However, there remains an interest in preserving Polari both as a matter of queer archiving and a little fun. Indeed, it’s a joy to speak for many gays and fag hags, rich with inuendo, double-entendre and the kind of vicious wit you expect from an old drag show down Brighton. Often spoken from the side of the mouth or from under one’s glass (bevy), it comes from a long lineage of influences, sharing much of the same legacy as British drag. Watch a little footage from Maisie Trollette, Britain’s oldest working drag queen, and you’ll hear it riddled among sentences as she reads her audience to filth with tongue in literal and proverbial cheek. Even now, Polari phrases crop up in common parlance. Trying to scarper from an overpriced dinner, using the khazi, or telling someone to naff off – Polari is a trusty linguistic device, ideal for adding a little zhoosh.

Today on #BetwixtTheSheets it is so bona to vada @_paulbaker_ & chat about the omi palone’s parlare! Didn’t understand that? Good! Because we’re talking about the history of Polari, the secret language of gay men when homosexuality was criminalised https://t.co/OrWhG68Hq7 pic.twitter.com/BEABzSX0kI

— Whores of Yore (@WhoresofYore) September 26, 2023

Before Polari, though, there was Parlyaree, a secret argot used among 19th-century circus performers – many of whom had come from Italy – to speak without punters understanding. This language, which was a major inspiration for Britain’s seaside Punch and Judy shows, further evolved at the end of the century when it began cropping up on merchant navy ships, in Victorian music halls and theatres. Here, users would throw in Yiddish, backslang and cockney to the Italian and Romani mix, forming Polari as we know it.

By the 30s, it became the lingo of choice for queens and underworld villains, remaining integral to the former well into the 60s. “It could be used as a form of information exchange in cruising spaces like parks,” says Paul Baker, the linguist behind Polari: The Lost Language of Gay Men. He points to the use of female names as code. “A hissed ‘Lily’ could warn others that the police were approaching, for example, and during a slow night, men might gossip in Polari about past and future conquests.”

View this post on Instagram

Baker, a gay man who was first acquainted with Polari by an elder during the 90s, was intrigued by the language and its gradual extinction. He correlates its decline with a number of factors, including the 70s Gay Liberation Front (GLF), which considered Polari the very embodiment of closeting. Another factor, he says, was its explicit use in BBC’s Round the Horne radio show broadcast during the 60s by Hugh Paddick and Kenneth Williams. The pair, who often caricatured homosexual men, were, by all accounts, practising queens, and Polari was their way of winking and nudging to a mainstream audience. “We’ve got a criminal practice that takes up most of their time,” they’d cackle.

Lavinia Co-op, a veteran drag artist in London and New York, was a part of the Gay Liberation Front, although she’s a firm believer and student of Polari. In fact, it was in GLF that she first heard terms being thrown around. By the 80s, she met an older queer who had worked on the ships post-war, and they gave her the lowdown. As she understands it, Polari thrived in this homosocial, panto-camp environment. “The captain of the ship would have a party, and some would dress up in drag,” she says. “Of course, it was okay as it was a performance.” Despite Polari’s characterisation as London-centric, Lavinia keenly notes its prevalence across the UK. It was “You alright, Mary?” down South, and “You alright, May?’ up North.

It’s a radical act, ditching assimilation for something a little seedy, un-American, and unlikely to be recounted in a corporate diversity campaign.

Princess Julia, the East London gay community’s fairy godmother, was also introduced to the language in the 70s, when she left school and took up work in a hair salon. “I worked for this fabulous queen, Willie, you know,” she remembers. Nowadays, she still slips it into conversation, regardless of whether others understand her. “I like the lilt of it,” she says with an inimitable Eastend drawl that lends itself to the elongated, suggestive vowels of Polari.

Because of its smutty nature, Polari can be learned as much from the words as the gestures and intonation that accompanies it. The phrases, “Definitely a touch of lavender there, dear,” “We’ve all heard, duckie,” or “I’ve got your number,” speak for themselves. Even the more cryptic numbers, such as bona aris, (nice arse) or trolling (looking for a hookup), can be picked up quickly as so much of their meaning relies on the context and its delivery.

View this post on Instagram

Young queens today are perhaps less accustomed to the language, although they will have witnessed it in dribs and drabs. That said, many of us have done a little research, if not just to reconnect with our heritage. Much in the same way that cottaging, cruising and sauna visits remain as popular despite otherwise more efficient alternatives to find love, Polari refuses to die. Yes, we can now get married, divorced and hold down jobs without our “lifestyle” getting in the way of that, but in many ways, we’re still drawn to our deviant pasts.

After all, it’s a radical act, ditching assimilation for something a little seedy, un-American, and unlikely to be recounted in a corporate diversity campaign. Being an omee-palone (a gay man) is to some simply a matter of preference – a tick and a cross on an NHS questionnaire, a taste for leather, or clang against the heterosexual matrix – but to those who know their history, it’s membership to a secret society that has queered the parameters of culture and language to survive. Next time you have an itch that needs scratching, don’t open Grindr, Scruff or Recon. No! Head to the dark corner of a bar, crane your neck, and utter to the well-tressed sailor on your left, “Oooh, bona riah” without any fear of Tracey Truncheon carting you off.

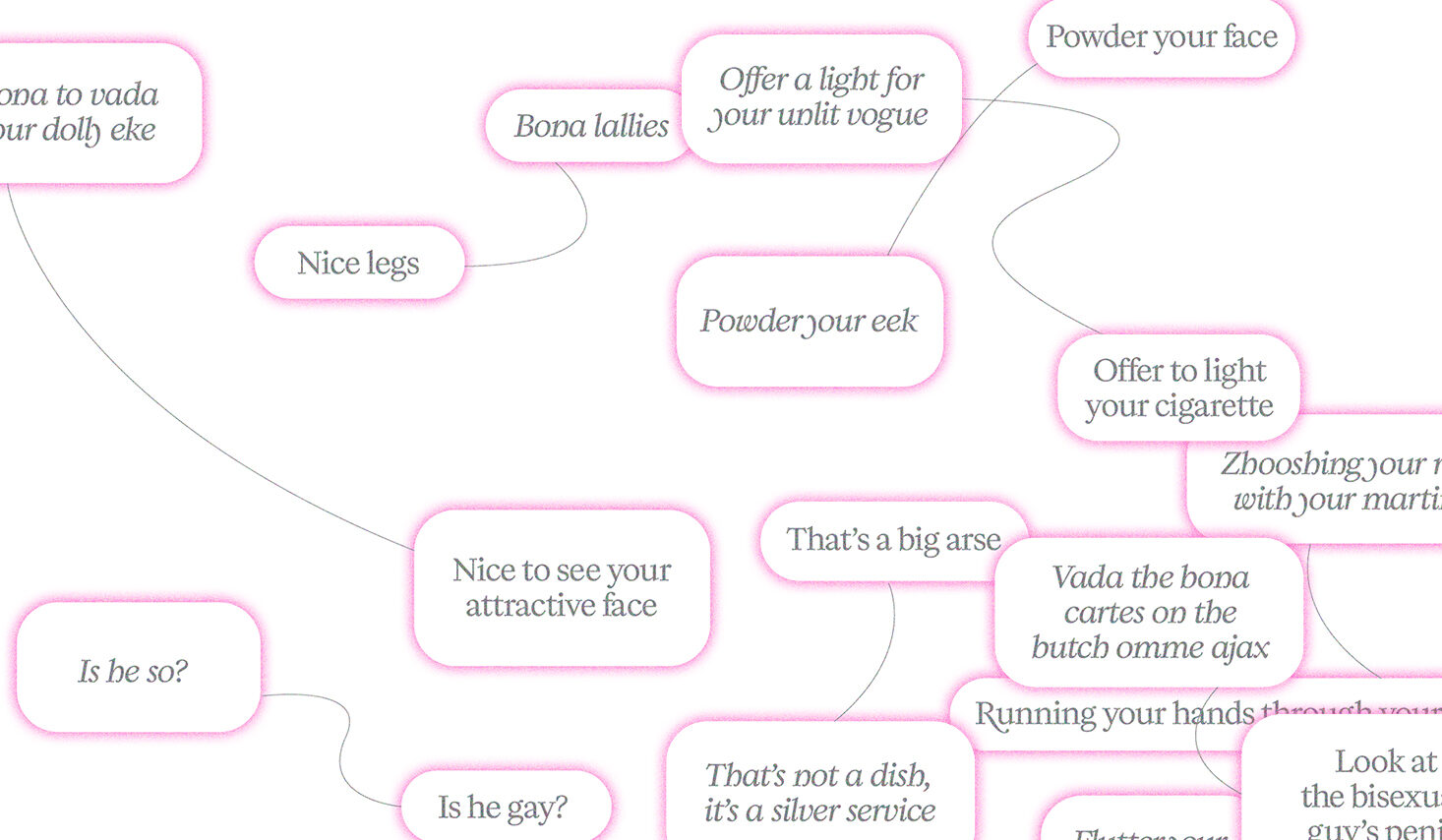

And, in case you need some pointers to get you started, here’s our guide on some key phrases in Polari

Bona to vada your dolly eke —> Nice to see your attractive face

Bona lallies → Nice legs

Is he so? → Is he gay?

Zhooshing your riah with your martinis → Running your hands through your hair

That’s not a dish, it’s a silver service → That’s a big arse

Naff riah → Bad hair

Powder your eek → Powder your face

Flutter your ogle riahs → Flutter your eyelashes

Offer a light for your unlit vogue → Offer to light your cigarette

Vada the bona cartes on the butch omme ajax → Look at the bisexual guy’s penis