It might seem like odd timing to be blogging about gay shame during LGBTQ Pride season – or at all.

But even as across the UK we celebrate progress, two books and a comedy special have delivered a message about mental health and wellbeing too urgent to ignore.

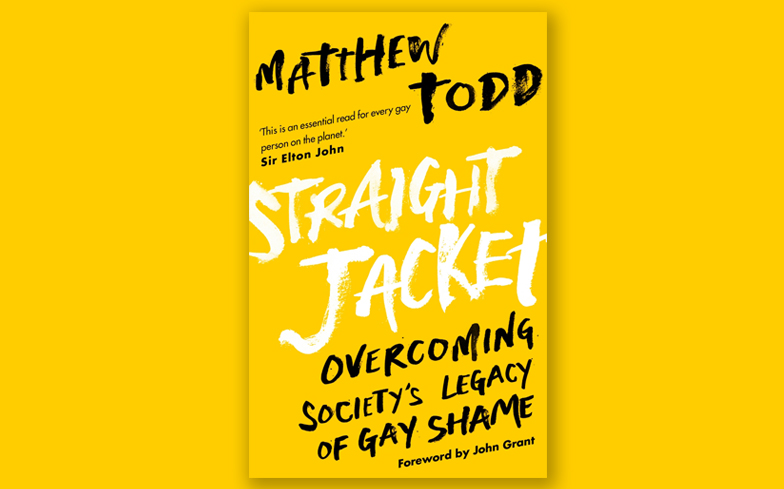

Matthew Todd’s book Straightjacket, Hannah Gadsby’s Netflix special Nanette, and Darnell Moore’s memoir No Ashes In The Fire document, in heart-breaking detail, how LGBTQ people continue to struggle with a legacy of shame inflicted upon them since childhood by societies that still don’t really accept difference and which deny them the need to be loved for who they are.

None of them are comfortable reading or watching. I suspect that all but the most fortunate of LGBTQ people will recognise their description of the intense loneliness and confusion that comes with growing up ‘different’. The pain of being told – by people who profess to love or want to help – that there’s something wrong with you. Of relentless pressure to change. And how that pain is then internalised, manifesting, sometimes years later, in poor mental health, low self-esteem and often damaging ways of coping.

But the crucial question posed by these books and television programme is what do we do to ensure that this cycle of shame ends and ends soon?

© Ben King / Netflix

Which is where this connects for me directly to the work we are doing at Barnardo’s and in particular our focus on mental health and wellbeing where we are putting front and centre the need to talk openly about and address Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs).

ACEs research shows that significant childhood trauma blights the lives of people on the same scale as the trauma inflicted by fighting in a war. And those feelings then play out in poor physical and mental health, addiction and anxiety.

These works remind me why it’s right that Barnardo’s work on well-being is looking particularly at the needs of LGBTQ youth.

Matthew’s book also makes a powerful case for one of Barnardo’s other key aims – fully inclusive relationship and sex education in schools. This is soon to become mandatory in England – something we have been campaigning for at Barnardo’s. We need now to make sure what is taught is of the highest possible quality and starts to address these issues early – not just for LGBTQ youth but all children and young people.

Personally, I would also like to see a commitment from schools to tackle trans/bi/homophobic bullying separately and never just as a ‘bolt on’ to general anti-bullying efforts. This would reflect that being bullied for being LGBTQ is very different and means children and young people have very different needs.

There are two common responses to this. The first is “but surely isn’t everything fine now?” It just simply isn’t true. If you don’t believe me, look around and ask whether almost everything that you see and hear on TV and social media still shapes a straight/cis view of what and who we value most and what we love (or consider loveable). Or how the language we use and the ideas we have, often without knowing it, communicate to boys and girls that there’s a way they should be (or not be) that reinforce that message.

This is the world that LGBTQ children and young people are growing up in and it is why the cycle of shame keeps turning. We need to ask ourselves not only how we tackle obvious or extreme manifestations of trans/bi/homophobia but also how the society we create – consciously and unconsciously – can give all young people hope and surround them with love and support.

The second response is “isn’t this too gloomy, not representative and, worse, risk playing into the hands of those who are opposed to equality?” It is of course true that there has been huge progress and many, perhaps even most, LGBTQ people live happy, fulfilled lives and have either never experienced, or have moved past, their adverse childhood experiences. That is a great thing and is to be celebrated. But as Matthew says in his book, we mustn’t keep denying what we know and that boldly facing and addressing these issues is in itself “an act of empowerment”.

And of course the very real impact of childhood trauma is not unique to the experience of LGBTQ young people. So nor is Barnardo’s work either.

Personally, these two books and a comedy special have helped me reflect on some of my earliest experiences and what I internalised growing up. It is making me re-think things I’ve too readily taken for granted and I’m grateful for that.

But most importantly they send a positive message that the future is never written. We can celebrate with Pride this season while also committing to stopping this happening – not just for LGBTQ folk but everyone. I’m proud of the work that Barnardo’s is doing on these issues.

Adam Pemberton is the Strategy and Performance Director at Barnardo’s. To find out more about the great work this charity does, visit their website here.