“More than anything, this book has been a love letter to these men, founded on a curiosity and appetite to know about people’s lives,” Jason Okundaye writes in the final pages of his outstanding debut, Revolutionary Acts. Indeed it is this curiosity and appetite, that steers Okundaye’s vivid and vital slice of Black gay Brixton society through the stories of several towering figures – Ted Brown, Dirg Aaab-Richards, Alex Owolade, Calvin Dawkins, Dennis Carney, Ajamu X and Marc Thompson.

As a prolific writer, Okundaye’s bold and masterful prose succeeds in transfiguring gossip – slick, mad, salacious, transgressive – into something numinous; his memory work bears all the hallmarks of divine enterprise. A sibyl of South London. Throughout Revolutionary Acts, the London-based writer constellates a history of Black gay Britain as exemplified by their unique but interrelated tales, while unearthing other notable figures from the 1970s to the present. These histories, Okundaye explains, cannot be told via the mere function of reportage and, so, through sharp interviews and thorough research, he brings accounts, past and present, to life.

Okundaye’s book is a meta and revolutionary act: through an onerous process of revising and recording oral histories with complexity and compassion at a time when many, young and old alike, speak nebulously of the necessity of intergenerational LGBTQIA+ conversations. Revolutionary Acts is a work of not just restoration but restitution. With flair and devotion, Okundaye illuminates and fills the gaps of the past obscured by time and neglect, and gives these men their much overdue flowers. It is no exaggeration to call the work he does here a rescue effort. He holds these men and their stories close and fast, lest they be lost to us for all time.

Okundaye reframes well-trodden platitudes about activism and the oppressed, recontextualising old, simple narratives by offering up complications. Revolutionary Acts is revelatory about the past, and prescient about the moment in which we live. The men in his book are not cookie-cutter saints or villains, not simply victims or perpetrators, but they’re laid out in all their mortal complexity. This is history not as time-capsule storytelling, but living, breathing entities showcased as something mercurial and imprecise, yet vivacious and highly gorgeous.

To mark the publication of his evocative debut, we spoke to Okundaye about the complex ethical dimensions of this kind of work, the decline of Black gay spaces of socialisation and its impact on the community and the rewarding process of building real and deep relationships with the men of his stories.

Revolutionary Acts is a triumph. Congratulations on such a poignant and timely debut. In its epigraph you quote Wilde: “History is merely gossip.” Can you tell us about the vital role gossip plays not just in the exposition of these histories, but in the formation of them?

I find gossip interesting in those times because as much as it spread, it was also contained in a way that it isn’t now. A piece of gossip would be passed around, sometimes to the right people, sometimes to the wrong people, but it would always be within a certain community and have a certain purpose. Now, you might see someone on Twitter post about how they’ve seen a celebrity at some gay cruising site.

As much as gay men [back then] might have gossiped about them amongst themselves, there was a kind of code of silence; you don’t go and bring this publicly or you don’t do some anonymous [story] and explode it. There are some examples of malicious gossip, but it was a lot more dignified and a lot more controlled. [At times] it was for protection, sometimes it was spite and malice, [but it was isolated from interlopers in a way that it isn’t now.]

There are complex ethical dimensions involved in writing this kind of book. How did you deal with recording the history of people who are still alive today, and people who often had conflicting accounts, not just of events, but also of each other?

The ethical question was at the forefront of my mind, from the outset of this research, because if you’re talking about Black gay men about their Black gay life, that is a sensitive topic. There are certain things they might tell you and they might regret later. I wanted to make sure that I had an open process with them and I didn’t want to jump in with an interview. I got to know them first and they also got to assess what their boundaries were, and what was appropriate to go into what they would be comfortable with.

The fact that there’s a period between interviewing them, me finishing the book, and the book coming out, when there was plenty of time to say ‘if there’s anything you said that you might want to take back or add, that’s fine.’ No argument, and no question.

Even in the selection process, when I was looking for people, I always had to make an assessment over whether it was appropriate to include that person. There was a person who I was keen to include because he spoke to Black British gay fashion. But, when I found him, he was not someone that I could interview or someone I’d want to get information out of. I kept up a relationship with him and still chatted to him and it was nice to connect on that level. I never wanted to present a singular history. I think it would have been worse if there was no other interpretation.

As a writer, how do you protect yourself and your interviewees, when dealing with often distressing subject matters like death, incarceration, myriad traumas, and acts of violence?

There were moments when we had to pause and check in with my interviewees. There was no one whom I interviewed on just one day to make sure that everyone was in their best state. It can be very draining to go through your entire life like that. I find it draining talking about what happened last week! So to go 20, 30, 40 years into the past is a difficult thing.

I didn’t think that much about protecting myself. I felt it was important for me to feel the weight of these things. If that translated into my writing then that’s good, because I didn’t want to have something cold and dispassionate. I wanted to show that as I was learning all this information, what the men were telling me, I was also feeling at the same time. I tried to show that the history was interactive and that information was being made in the moment.

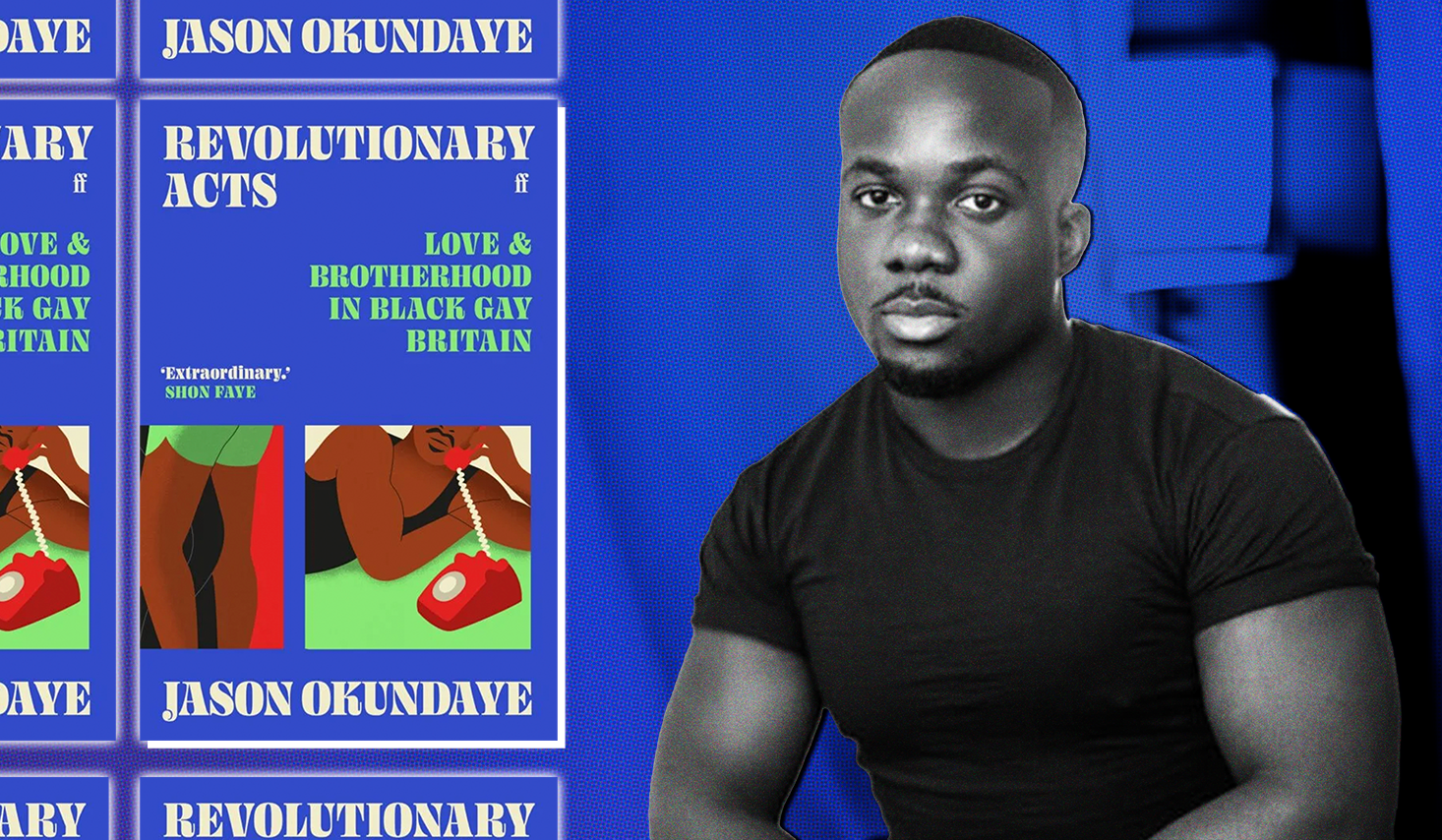

I’m so pleased to reveal the cover for REVOLUTIONARY ACTS: Love & Brotherhood in Black Gay Britain.

This is a social history of Black men who lived openly and daringly, come and meet them.

Pre-order your copy, arrives 7 March 2024 ❤️☎️ @Waterstones https://t.co/BVIltSbp3K pic.twitter.com/usej8PWfP2

— Jason Okundaye (@jasebyjason) November 27, 2023

There has been a noticeable decline in brick-and-mortar spaces for Black gay men to build community in the way they existed in the 70s, 80s and 90s. How is this affecting their experiences and how unfolding history is being recorded?

Back in the day, it was a mixture of things. You had people who owned houses so were able to house people, were able to have those parties, because they have those spaces. It’s interesting, I used to go to a lot of lesbian house parties pre-pandemic and I really loved them. Recently, I was reflecting with some friends who were like: ‘What actually happened to those?’ Then, we were like, ‘Well, the pandemic happened and no one has a house anymore.’ People’s financial concerns changed, and no longer could they be living in a houseshare with friends, or a flat by themselves. Now people move back home with their parents, or they just don’t have the money to be able to put these things on, they just don’t have the space anymore.

There may be criticism of the book’s narrow focus on the lives of Black queer men – and interpret it as an exclusion of the Black women who were also key figures and activists in those times. How do you respond to that?

I wanted to write history that was very specific and was very focused. I was very deliberate about the fact that I wanted to write about people who were like me, however, many years ago. Originally, I thought I could do this big, sweeping broad LGBTQ narrative. But the Black lesbian story is incredibly complicated in the sense that it’s tied up a lot with a woman’s movement, lots of different organisations pertaining to motherhood, and that kind of organising. I remember thinking: ‘This is not my place to write this history at all.’ If someone were to write that book on Black lesbian history or Black trans history, I’d be so supportive of that – I don’t think that I should take up that space or dominate the conversation. I wanted my book to be focused. There are so many books which focus on one specific group and there’s never that same obligation for these writers to account for everyone. I wanted to unapologetically be like: ‘This is who this book is about. Everybody can read it, but these are the limits and constraints of it,’ and not apologise for that.

What advice would you have for any young people who read your book and want to embark upon this kind of memory work – what would be your guiding words?

There’s nothing I would do differently. This process happened as it was meant to and I was quite happy with how it happened. It was very organic. It’s almost something that happened by accident. I didn’t necessarily think that I was going to end up writing this book. [Embarking] on a similar journey requires a real openness to just reach out to people and not be afraid to be friendly to [them], not to see people as just subjects to extract information from but to think about building relationships with them. Think about what the value of a good conversation is for two people. Having that as a kind of framework means you can get the most rich and textured details out of people, and you will want to continue the relationship when you’re well past the point of completing the project. I would say just go for it, do it, and don’t make any assumptions about what’s out there – you’ll be surprised by what you will learn.