Welcome to Queer by Design, a new monthly column by GAY TIMES Contributing Editor Jamie Windust. Here, Jamie profiles emerging designers about the intersections of style, identity and expression and how these factors inform their creative practice.

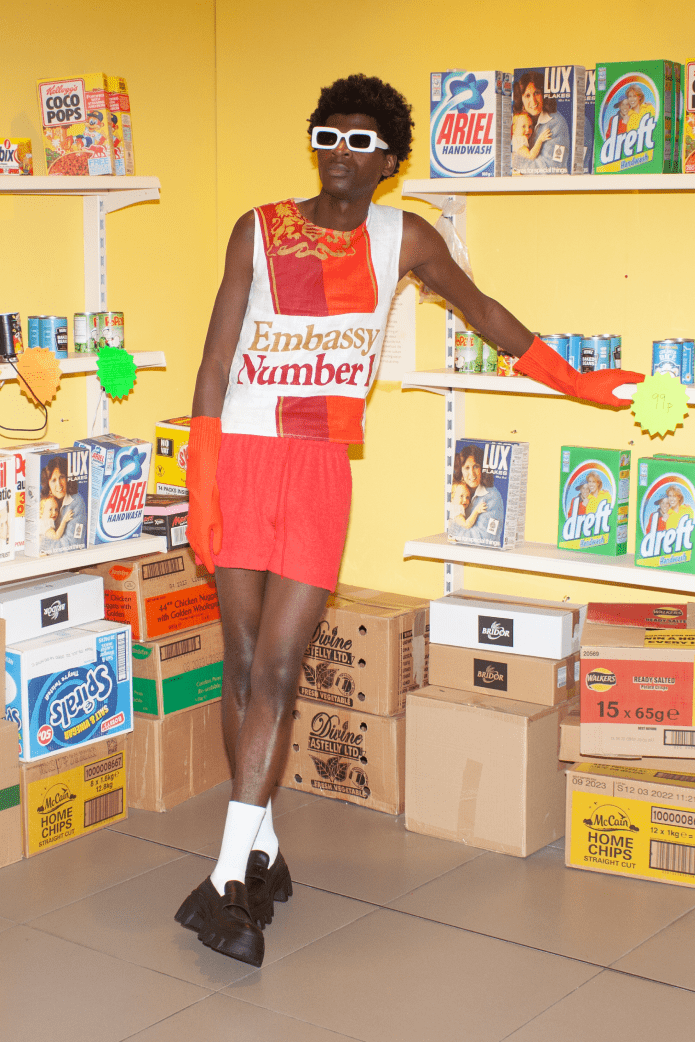

Adam Jones and his eponymous brand have become something of a cult classic, in no small part thanks to the IYKYK appeal of his beloved vests – brightly coloured garments made from upcycled beer towels and featuring the names of classic alcohol brands.

They’re a walking advertisement for the nostalgic appeal of pubs: a place to hunker down with a Guinness or two and tuck into some roast spuds on a Sunday. And although Jones’s signature design has been worn by the likes of Dua Lipa and Barry Keoghan, they take inspiration from the designer’s upbringing in the small, small village of Froncysyllte near Wrexham.

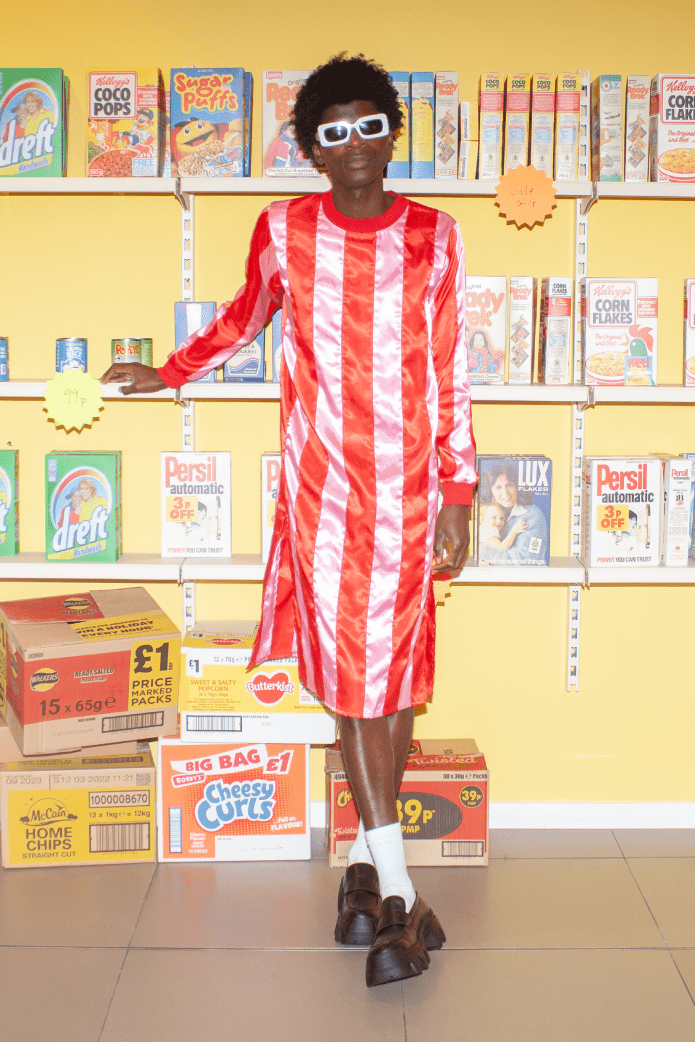

And it’s not just boozers that have whet the Welsh designer’s creative whistle. From PE kits to your granny’s doilies, Jones toys with the iconography of British life to exhilarating effect. Take a pair of silky football shorts which, with the simple addition of a white lace trim, shrugs off the machismo and rigid gender conventions associated with the beautiful game. Playful and irreverent, Jones’s work draws unexpected contrasts, splices up established meanings and ultimately encourages deeper reflection on baked-in ideologies we take for granted.

Jones’s most recent collection gives even more food for fashion thought. The aptly titled ‘Corner Shop’ showed off-season in October and pays homage, one primary-coloured apron at a time, to the fishmongers, butchers and grocers of Deptford High Street. At a time when gentrification is sweeping through South London’s communities, bulldozing small businesses to make way for Costas and luxury flats, this celebration of the area’s vendors feels touching, timely and very much needed.

Intrigued by Jones’s camp humour and tongue-in-cheek references, GAY TIMES caught up with the designer to chat about the egalitarian power of the pub, learning to celebrate his queer identity and whether subverting gender norms in his work has changed his own relationship to masculinity.

Your work evokes such a nostalgic reaction for so many people who grew up in pubs and working men’s clubs. Would you say this is a form of reclamation? Or is it more of a celebration?

I did grow up in these places but as a child it’s somewhere I felt intimidated or didn’t enjoy being dragged to. It was only when I got older and moved away from home I looked for comfort in the familiarity of these places. I think it was a backlash against the glitz and glamour of London and swanky bars, which perhaps intimated me more than a pub did. I wanted to find a place which reminded me of home and I grew to love the pub.

It’s that typical thing of wanting to get away from where you grew up and head for somewhere more exotic, but then you’re drawn back to what you know, you miss the old man pubs you didn’t take advantage of when you were there. I think the pub is one of the only spaces that is democratic, there’s no bouncer or door policy – anyone can go. It’s the one place you speak to people you maybe normally wouldn’t, or meet characters you don’t usually surround yourself with. I just love the mix of people that share in the joy of a pint. Once you cross the threshold everyone is welcome.

Many designers who are part of the LGBTQIA+ community use their identities or community experiences within their work. Was this something you found you wanted to do?

I don’t think I do that consciously. I should probably think about it a lot more. Most designers historically are gay men, so it’s not a difficult industry for me to fit into personally, not now that I am comfortable with being a gay man. Saying that, there was always a certain trepidation to begin with, wanting to enter the world of fashion. It felt like choosing this career was basically me outing myself, which I was not ready to do and found scary as a young boy in Wales.

So I guess the decision to go for it and take the risk – as it felt it was back then – was a brave one for me, so now I’m just very proud to be gay and a fashion designer, which is a tag I was terrified of. I got into designing clothes because it’s something I have always wanted to do, I didn’t really really see it as embracing my sexuality. As I say, if anything, I was terrified of my sexuality; I just wanted to make clothes.

One of your early supporters was Judy Blame, the late stylist, designer and icon of London’s punk and queer scenes. What kind of impact did he have on you?

Judy inspired me so much. I had never met anyone in the industry like him, his ‘fuck you; attitude, the way he took the piss out of industry figures and laughed at himself was so refreshing to me. He didn’t take anything too seriously, except the work, that’s all that was important. It’s exactly how I felt; he encouraged me, took an interest in what I was doing and that allowed me to feel happy sitting on the outside. He made me feel it was cool to not be accepted by a dated industry, to do things my own way. If he liked my work, I was happy.

Has your own relationship with masculinity changed at all since you’ve had your brand?

Although my brand is for everyone, I find it more exciting to see my pieces on a traditionally ‘masculine’ figure. I think I have become more masculine, weirdly, as I grow up, which I can’t explain. I was definitely not a masculine child, a masculine teenager or a masculine young adult. I guess I’m more comfortable being masculine as the world progresses. I saw masculinity as something intimidating or maybe aggressive growing up, I was never one of the lads, so it was very ‘other’, but now I do feel masculine in my own way.

Sometimes I worry I would fit in too much in my hometown now, which is a worry! Sinking a pint with the old fellas. I don’t find masculinity scary anymore, I’m interested in it, and inspired by it. What it is to be traditionally masculine, or the way a man would dress without thinking too much about what they’re wearing to go to the pub for example. It’s also fun to twist it a little by adding a feminine touch to something traditionally masculine, there’s a lot there to play with, like a lace frill on a pair of footy shorts, almost taking the piss out of the hyper-masculine or just softening it.

What’s the most important thing for a young designer to have as part of their mindset?

Don’t try to run before you can walk. Just focus on what you want to do and not really how you’re going to get there. Just do it, trust your instinct, do what you want, do the work and see what happens.

Finally, what would you say to emerging LGBTQIA+ designers who want to start their own brands but who struggle to overcome the red tape that can often guard the industry?

Cut through the red tape. Don’t preoccupy your mind with what the industry considers to be the norm or the route to go down, just make what you want to make and people will notice. The right people, the people who like what you do and respect you and want to be close to what you do are the important ones. You can waste a lot of time being concerned with how this industry works and what it means to be a part of it.

I just want kids to be more punk and disregard the rules a bit. Dream big, it’s like the hare and the tortoise, slowly but surely you can do what you want to do, it just takes time. It can take a lot of time, but that’s ok. You need patience, perseverance and passion.

Check out Adam Jones’s newest collection here