Earlier this week, the Kunlun Group completed a full buyout of gay hook-up Grindr in a deal which totalled $245 million.

The Chinese company initially bought a 60% percent stake of the business for $93m back in January 2016, and have now acquired the remaining 40% for $152m.

Following the completion of the deal, Grindr confirmed that Kunlun executives will now take charge of the company.

This means that former CEO and founder, Joel Simkhai, will exit the company, with Grindr’s current vice-chairman Wei Zhou named as executive vice-chairman and CFO, and former Facebook and Instagram veteran Scott Chen to join Grindr as CTO.

However, former US intelligence officials fear that Chinese intelligence could now seek access and track personal information of millions of Grindr users.

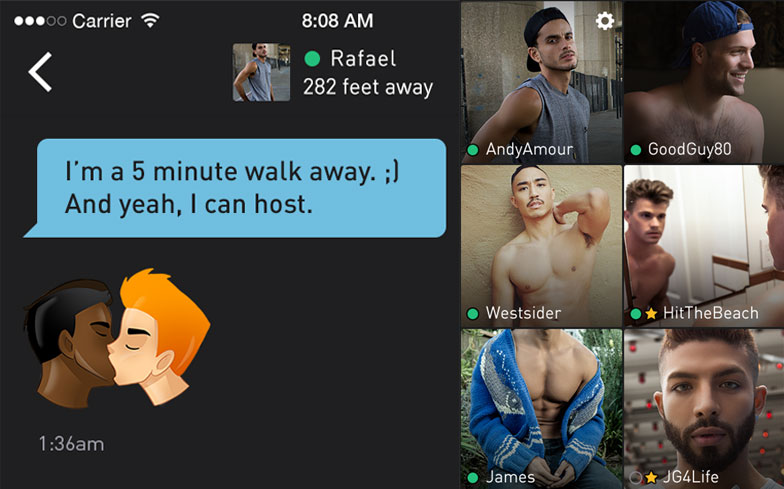

The hook-up app boasts 3.3m daily users, with private data including location, messages and pictures exchanged on the platform.

The Washington Post reports that the Chinese government are hoovering up massive amounts of data on their own citizens, as well as people all over the world, as part of an effort to build files for intelligence purposes.

“What you can see from Chinese intelligence practices is a clear effort to collect a lot of personal information on a lot of different people, and to build a database of names that’s potentially useful either for influence or for intelligence,” said Peter Mattis, a former U.S. government intelligence analyst and China fellow at the Jamestown Foundation.

“Then later, when the party-state comes into contact with someone in the database, there’s now information to be pulled.”

However, Grindr’s vice president of marketing, Peter Sloterdyk, asserted that the privacy and security of users’ personal data is top priority.

He added that because Grindr remains a US company, it will be governed and protected by the laws of the United States.

That being said, the report added that Chinese companies are subject to control by officials in Beijing to hand over data in the interests of “public security”.

The definition of “public security” is usually as wide as the Chinese government wants it to be, so companies are likely to have little choice but to comply.

“What we need is more clarity on the implications of these sorts of purchases and what it means for non-Chinese citizens,” said Shanthi Kalathil, director of the International Forum for Democratic Studies at the National Endowment for Democracy.

“At the very least, if you are thinking about blackmailing individuals or compelling people to act in a certain way, that information is incredibly valuable.”