When I started to properly come to terms with my sexuality in early 2017, I began what I feel is probably a queer rite of passage: I devoured every LGBTQ+ book and film I could reasonably afford.

If I could’ve swept my local bookshop clean of all such works I would have, but alas it was a very small Waterstones, and an LGBTQ+ section didn’t even exist.

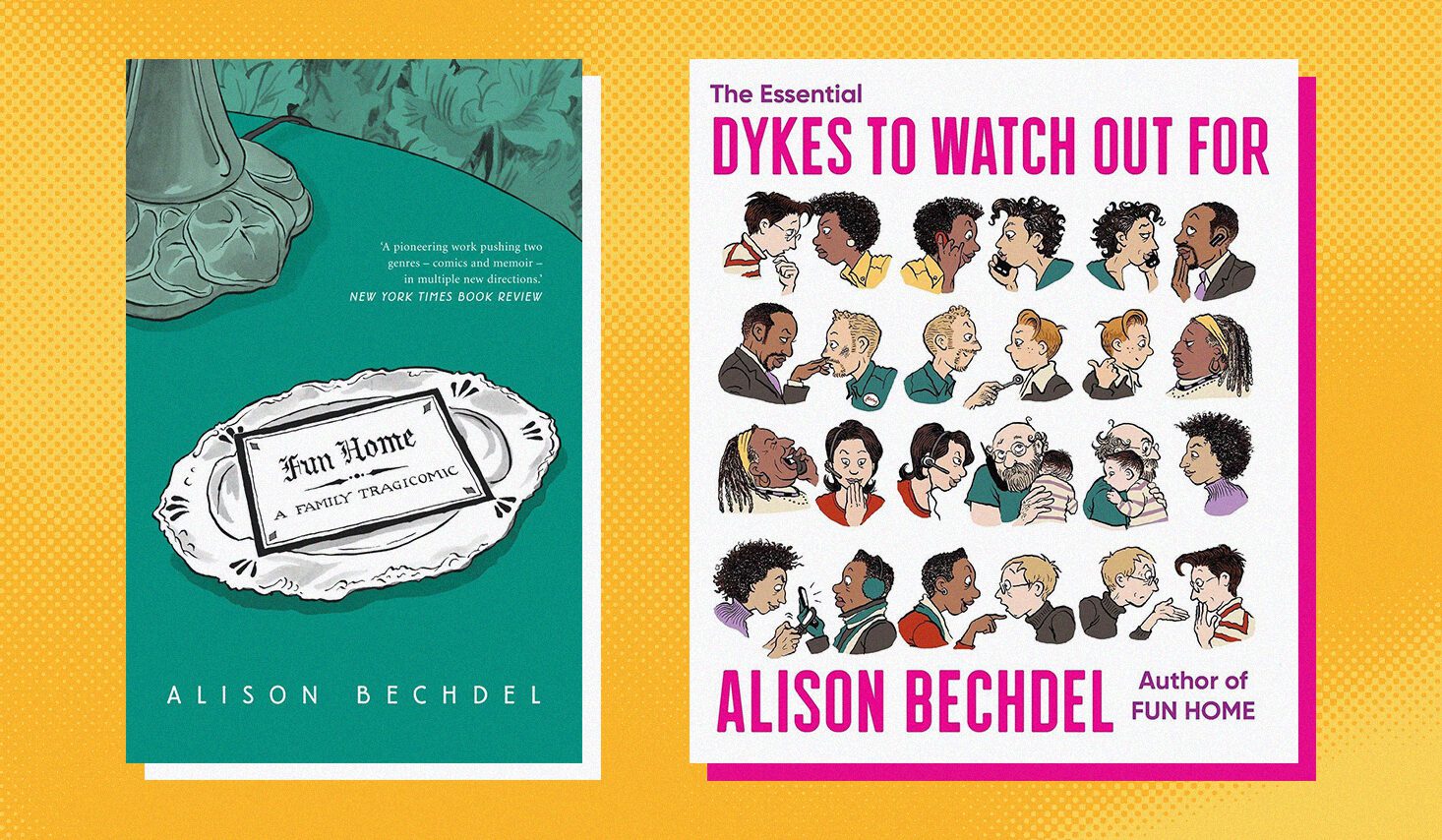

Among the most illuminating pieces I came across on my quest to understand were the graphic novels by the incomparable Alison Bechdel.

My journey all started with The Essential Dykes to Watch Out For – a compendium of Bechdel’s serialised comic strip that ran in gay and lesbian newspapers from 1983 onwards.

The strip chronicles a group of queer women and their “lives, loves, and politics” in an ambiguous city rumoured to be Minneapolis. I read it lightning fast, cover to cover, and felt an enormous loss when I finished it. ‘No matter,’ I said to myself, ‘I’ll see if she has written anything else.’

Luckily she had. I had Bechdel’s first graphic memoir, Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic, in my hand within a week of finishing the last book, relieved that the ride I was on wasn’t over just yet.

About halfway in, on Chapter 4: In The Shadow of Young Girls in Flower, there was a panel that stopped me in my tracks.

She had illustrated a five-year-old Bechdel sitting in a window-side booth inside a diner with her father. A masculine-presenting woman stands at the counter, waiting for an employee to sign for the delivery she was making.

The caption read: “I didn’t know there were women who wore men’s clothes and had men’s haircuts. But like a traveller in a foreign country who runs into someone from home – someone they’ve never spoken to, but know by sight – I recognised her with a surge of joy.”

I sat and looked at that panel for a long time. I had gone through a lot of queer media by that point – But I’m a Cheerleader had been acquired on DVD, I watched LGBTQ+ Youtubers, I had read about Oscar Wilde, but nothing until this panel had resonated with me on a deeper level.

What Bechdel was saying wasn’t what I thought I needed to know to fit in, it was what I felt. What I had experienced. I had never been in a relationship, never been in love, but I had felt the thrill of recognition seeing butch women out ‘in the wild’ throughout my life; probably before I had any concept of what a lesbian was.

These were incredibly rare glimpses – out in the London Underground whilst rushing to change tubes, waiting to leave the screen at a cinema as the credits played and the crowd surged for the lobby. Women I would never meet, but had meant so much to me.

On top of this striking shared experience, I came into contact with so many identities for the first time through Bechdel’s work – Janis and Jerry were the first trans characters I ever saw actively transitioning from comic strip to comic strip, and how I really learnt what transitioning was.

Sparrow was the first queer woman I ever saw question her sexuality again after years of only dating women, and how difficult she found it to make her friends understand what she was going through due to their preconceptions made it all the more real. The narrative I knew up until that point was that once you came out, a line was drawn in the sand, and you didn’t look back.

These characters are all the more convincing because they are flawed, and maybe that is what I needed to see as a ‘baby gay’ with zero community to learn from in person.

Now when I look in the mirror, I see my reflection morphing more and more into what I saw in those fleeting glances I had when I was younger, and I recognise myself with a surge of joy.

Bechdel’s books were an integral part of my LGBTQ+ journey and helped me to develop a greater understanding of what it means to be a part of this incredible community full of diverse identities.

Everyone’s journey is different, but one thing that makes it a whole lot easier is having someone who says, ‘you’re not alone in how you feel’. Alison Bechdel and her writing did that for me, and volunteering with Just Like Us is allowing me to do that for other LGBTQ+ young people.

As a Just Like Us volunteer, I give school talks with my short hair, denim jacket and black boots. Getting to be a literal Dyke to Watch Out For is incredibly rewarding and I’ve loved every minute of it. I know it has meant a lot to the students I’ve spoken to, and I couldn’t recommend the experience highly enough.

Visibility is more powerful than anyone can express in just one article, but Just Like Us is the living proof of the change it can make for LGBTQ+ young people.