Imagine your dream world – what does it look like? Would you lean into your Willy Wonka fantasy and frolic through a tasty, saccharine wonderland? Perhaps you’d move your friends and loved ones into a mansion, laughing your way through life with your chosen family. You could go simpler and conjure up a world without work, in which you can binge-watch Real Housewives and eat Pringles to your heart’s content. Whatever the specifics, you’re probably envisioning a kinder and more accepting world than the hellscape we live in currently. It’s bleak, to put things lightly: the UK has been named one of the worst places in the world to be trans and we’re living in an ongoing climate crisis. In this context, utopian thinking isn’t apolitical; in fact, it’s deeply political, amongst the flames, to ask yourself: what would your perfect world look like?

The word utopia itself is an interesting one, which translates loosely from Greek to “no place,” and sounds extremely similar to the word for “good place.” Writers and philosophers have fused these definitions, conceptualising utopia as some mythical, paradise-like island; it’s a tease which represents a vision of perfection, one that remains ever so slightly out of grasp. In this sense, it helps to think of utopia as a motivating factor or driving force, something to actively strive towards.

More recently, queer academia has refashioned utopia into political praxis, a powerful tool in the arsenal of marginalised communities. Society feeds us the lie that today’s cruel world is fixed and unchangeable, that we should keep our heads down and just be realistic. We’re told to keep our heads down, to be happy with the crumbs we’re given. These lies are told tactically, to drill into us that there’s no point in imagining a better future. Thankfully, queer trailblazers have seen through these myths, especially over the last few decades.

Artists and scholars like Cuban-American José Esteban Muñoz have leaned into the possibilities of utopian thinking. Back in 2009, Muñoz released his game-changing book Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity, a wild ride through queer nightlife, performance and theory. Building on his past work on ‘queers of colour’ politics, Muñoz argued that queer theory had lost its bite; that the revolutionary politics of the ‘60s and ‘70s had been replaced by beige, capitalist thinking. No longer were we fighting to dismantle capitalism, fuck freely and abolish the police. Instead, we were campaigning for gay marriage and inclusion within lethal systems of injustice, like the military industrial complex. Muñoz’s core thesis was that the “utopian function” of queer theory had been lost, that we were being too pragmatic with our goals.

Cruising Utopia isn’t quite as horny as the name suggests, but it’s no coincidence that Muñoz looked to queer nightlife and culture for his source material. Already, we can – and do – build temporary havens, where we can briefly experience euphoria on sweaty, jam-packed dance floors. Culture and community can offer us the tools we need to build our own versions of utopia, complete with drag, dark-rooms and spaces to express ourselves without fear of judgement.

As well as nightlife, photography can be a tool for creating a queertopia. With nothing but a camera and a concept, artists can carve out images which embody their dream worlds. Even this process can be utopian. It’s a chance to gather queer friends and communities together, building temporary sets drenched in ethereal beauty, free from the chaos and the hatred of the outside world. There’s also the joy of being viewed through a queer lens. Too often, we’re reminded that mainstream society views us as an aberration, our identities as an affliction to be cured –– as exemplified by the government’s longstanding refusal to ban conversion therapy.

Photography and visual arts can give us autonomy. They can create a safe space for us to express ourselves however we choose, and have the beauty in that expression drawn out. Sometimes, there’s no better feeling than looking yourself up and down, smiling broadly and knowing in that second that you are the moment. It’s a magical feeling to be truly understood, to be seen and uplifted. In these dreamy bubbles of queer arts and community, that utopian dream can be realised.

Filmmakers have similarly taken the idea of queertopia as a creative prompt. In Queer Utopia: Act I Cruising, director Lui Avallos creates scenes in which queer elders are listened to, honoured and cherished. These spiritual moments speak to the power of collective memory – and although it might not always feel like it, his work underlines that there’s actually something pretty special about queerness. We’re part of a wider lineage, one rooted in mutual aid and collective care.

It’s all well and good to think of your utopia, whatever that might be –– but what’s the point? To go back to Muñoz, it’s all about broadening our worlds and allowing ourselves to spell out what our versions of paradise look like. Because, let’s be real, the world is a shitshow. The cost of living crisis is never-ending, mental health support is still nigh-on impossible to access freely and we’re glued to our smartphones in horror watching endless violence unfold in real time. We all feel the impulse to do something, and we should – we can protest, form direct action groups, create mutual aid projects and tactically boycott companies enabling this mass violence. Utopian thinking doesn’t have to mean taking a blinkered view and imagining a world with no adversity. In some cases, it’s the act of working towards a better future that creates the utopia.

Being apolitical is a luxury. Plenty of queer people worldwide don’t have the privilege of resting on their laurels, because they’re continuously under attack. There’s a value and sanctity to existing queer spaces, but they don’t have to be sanitised or apolitical to be utopian. There’s even something cathartic about coming together in the face of adversity, falling in love with each other – whether platonic, romantic, sexual or a mixture – and creating our own support networks to collectively battle adversity. Queertopia can – and does – exist even in today’s world. The real utopian project is thinking of how to extend those moments of bliss, to let them trickle into other dimensions of our daily lives.

After all, even in the utopian imagination, a life without adversity would ultimately be boring. We need to experience life’s lows to appreciate its highs. There’s nuance needed here, obviously – in a utopian world, the ‘low’ might be feeling fed up and tired, not being legislated out of existence for the mere fact of your identity. Yet today’s definition of queertopia can be distilled into moments of queer joy. It’s the euphoric high that comes from being loved for who you are, of being surrounded by others who make you feel seen. It’s a feeling that’s sometimes organic, like nestling into the grass on a warm summer day. But it’s also a state that can be cultivated, as we’ve seen throughout this essay.

So, as events continue to unravel, this year’s GAY TIMES Honours will put some respect on the name of queer trailblazers bringing their visions of utopia to life and sharing them widely. We’ll showcase the change-makers keeping their eyes fixed firmly on a brighter future and building their own versions of paradise in the meantime. This process is ongoing – and it should be! The path towards utopia is ultimately never-ending, but by imagining the world we want to see, we can gradually create the conditions to make every step forward feel that little bit lighter.

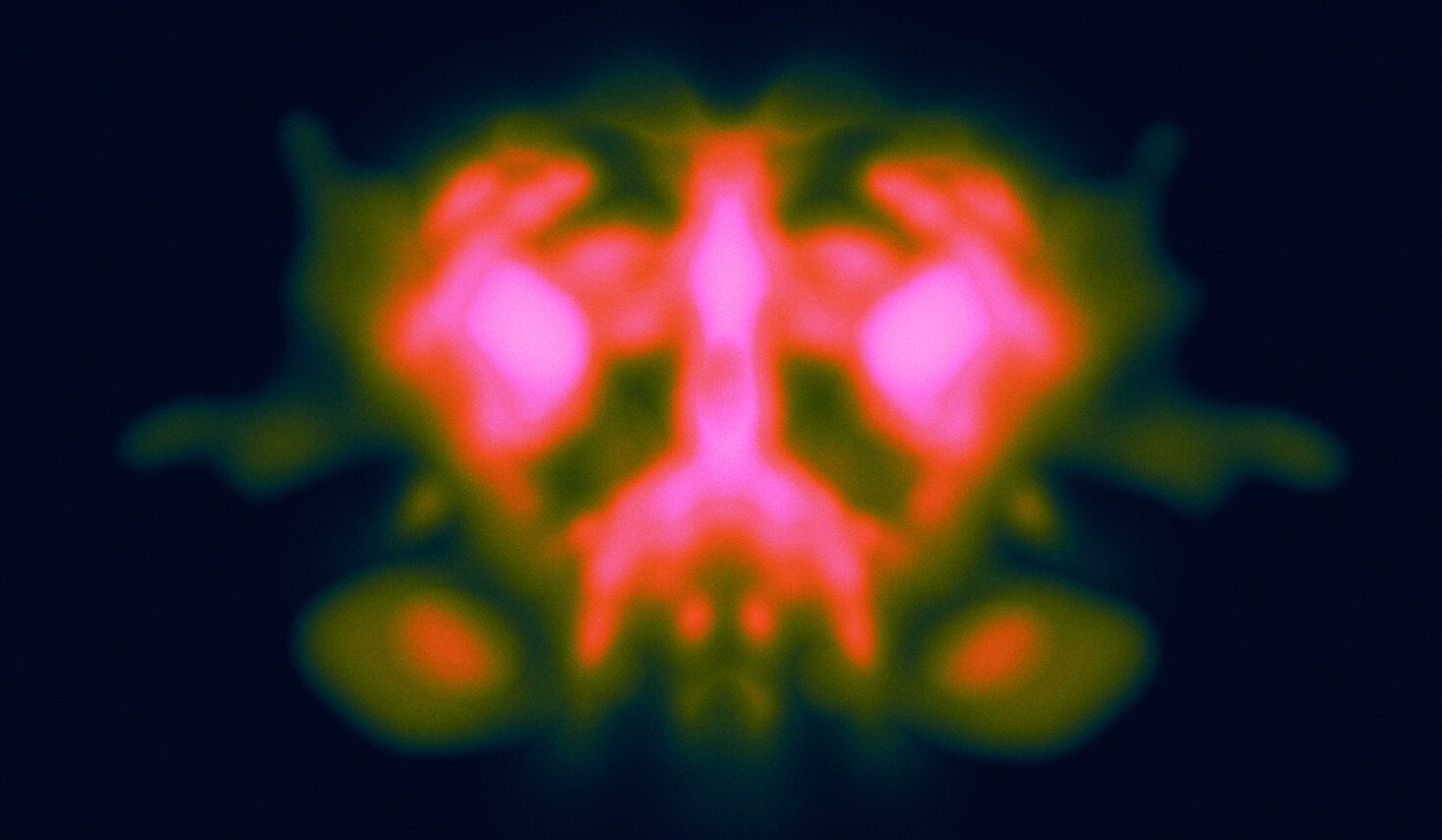

This very sentiment is what inspired the motivation behind our five GAY TIMES covers paying homage to extraordinary LGBTQIA+ talent. Inspired by elemental themes, each cover spotlights a star and their unique identity. For this year, our round-up of names includes actor Jonathan Bailey, American artists Slayyyter and Dua Saleh, UK MP Nadia Whittome and our digital Honours host Nick Grimshaw. Our custom designs for each cover encapsulate their trailblazing mark on the community. Embossed with a Rorschach-inspired illustration, our honourees are a reminder that queertopia looks different for everyone.

Together, let’s raise a glass to the queers refusing to lower their expectations and uncritically accept today’s shitshow as the best we’ll ever get. By striving for a utopian future, we can make the present feel that little bit more bearable.