When I was about 16, I started realising I wasn’t straight and I struggled to accept that. I thought I had to figure out exactly which label was 100% accurate and stick with that for my whole life.

Anxiety about committing to a label meant I put off figuring out who I am and continued thinking of myself as straight, even though that was obviously not true. Finding the right language for me seemed like an impossible task.

After many sleepless nights, I gave up trying to figure out exactly what I was feeling, and went through the very logical thought process that I didn’t need to commit to the most accurate label to start using one that is more accurate than calling myself heterosexual. The idea that labels were there to help me rather than limit me to one definable category was revolutionary for me.

Years later, I now talk about these concepts of self-acceptance in schools with Just Like Us – the LGBTQ+ young people’s charity – so I really thought that I would not have to re-learn the same lesson for myself again. I was wrong.

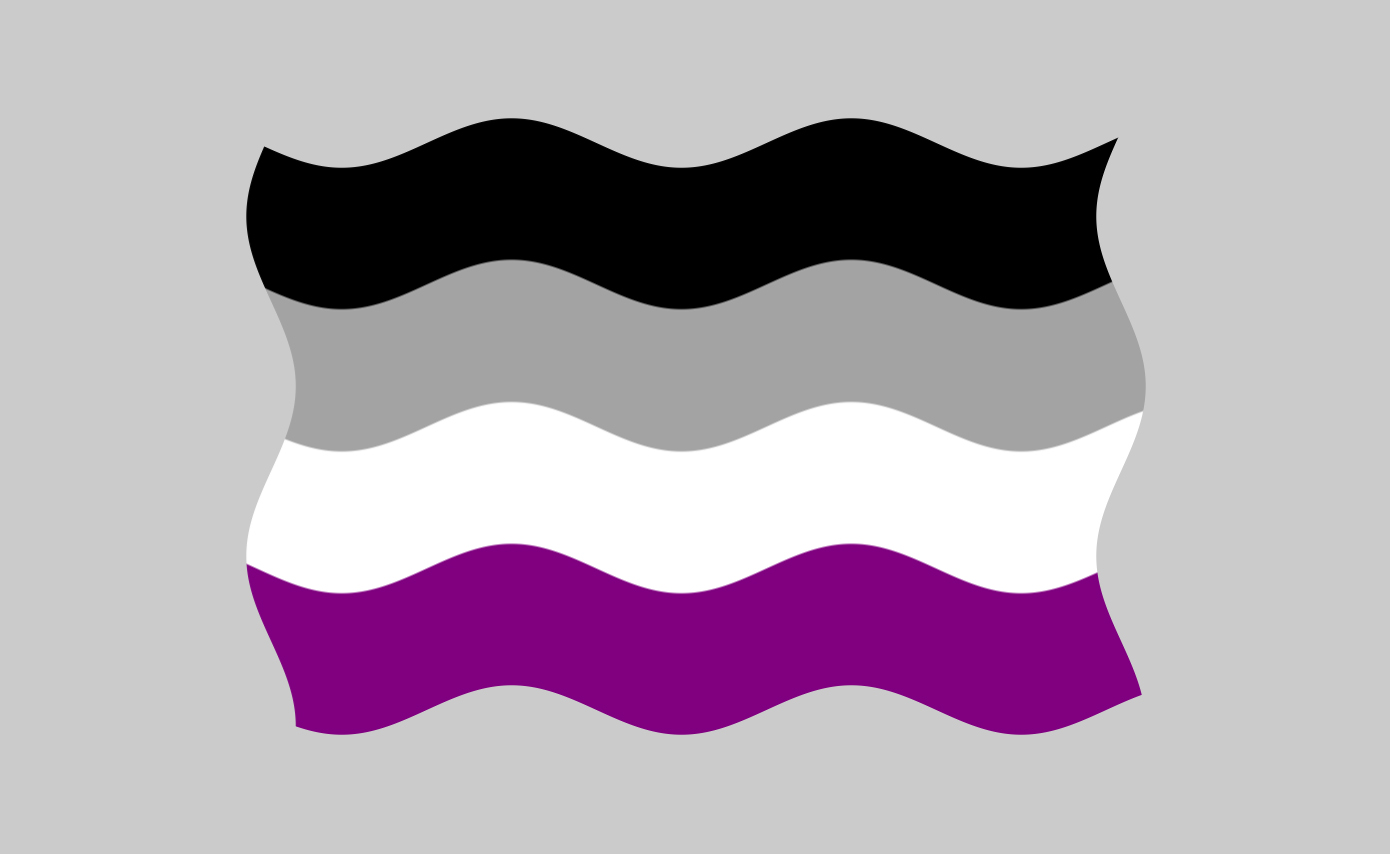

I recently realised that I am asexual as well as a lesbian. And honestly, I was a little annoyed that I was having the same issues all over again – trying to find the right language to encapsulate how I feel and who I am was a stressful journey that I thought I had already learnt how to deal with. I resented having to re-learn the same lessons.

Asexuality is when a person doesn’t experience sexual attraction to other people. That doesn’t mean they don’t experience other types of attraction, like romantic attraction. Neither is it related to levels of libido. It just means that sex isn’t the natural conclusion from feeling attracted to someone. That’s how I think of it for myself, anyway.

I’ve known that I’m asexual for about a year now, but it is still much harder for me to say than it is to tell people I’m gay. That’s why this article is written under a false name, and that’s why I haven’t told my family, even though I know they would do their best to be supportive.

I’m not sure why I find coming out as asexual so much more difficult – I know that asexuality is nothing to worry about nor be ashamed of. More than that, I know that all LGBTQ+ identities are beautiful things to be celebrated. Despite knowing all of this, I still can’t quite believe it and accept it about myself.

This is called internalised aphobia. I have picked up on society’s prejudice against asexual people and the general obsession with sex as an essential part of a healthy person, and absorbed it so it’s an internal emotional reaction that I cannot control. It’s not a conscious thought process that disappears because I understand that it isn’t true.

As someone who has spent the past several years in full-time science education, the idea that I still emotionally believe something that I know is not true goes against the grain. The culture in my school and university taught me to value finding rational solutions to all problems.

This has served me well in the past – even coming to terms with being a lesbian I did via logical processes – but this problem of internalised aphobia is not solvable with any amount of logic. It’s something purely emotional I have to work on.

I’m not going to pretend that this is a good thing, or that I’m okay with having internalised aphobia, because it’s not where I want to be. I want to feel pride in being asexual.

But I’ve also decided to forgive myself for having internalised aphobia. I’m not going to be ashamed of not yet being 100% okay with my identity because I know from experience with coming out as a lesbian that pride doesn’t come overnight. It doesn’t just land on your doorstep – it’s a process of learning and unlearning.

I’m going to keep working on embracing my asexuality and I have faith that, one day, I will have the same amount of pride in my asexuality as I do in other aspects of my queer identity.

We have to recognise that we’ve all grown up in a society that shames us from being different to the ‘norm’ of straight and cisgender. Aphobia seems ever-present, whether it’s people making jokes about virgins, or speculating about what might be wrong with a person if they’re an adult who hasn’t been in a sexual relationship before. So it’s no wonder we have internalised aphobia to unlearn.

I also think about young people in schools who I speak to as a Just Like Us volunteer. I would never judge a young person for struggling with internalised anti-LGBTQ+ phobias, so I’m going to not judge myself either.

I already know that asexuality is something to be celebrated, but self-acceptance is an emotional journey too, and I’m ready to embark upon it.

For more information about Just Like Us and their incredible work supporting LGBTQ+ youth, visit their website.