At its best, modern Britain is a multicultural mix of communities interacting and respecting each other while sharing an overarching British identity. At its worst it can be a collection of communities which view each other with animosity and even racial prejudice.

LGBTQ people from a Black, Asian, or minority ethnic background are at the intersection of this conflict, sharing an overlapping experience of racism, sexism, and homophobia which, in some cases, is perpetrated by members of the LGBTQ community itself.

The history of Britain is one of colonisation. Across hundreds of years Romans, Anglo-Saxons, Vikings, and Normans successively settled in the British Isles and contributed to the cultural and genetic makeup of the island. In turn, when a British state and identity was formed, Britain became the colonisers, sweeping up almost a quarter of the world’s population and landmass in the largest empire the world has ever seen.

It was the legacy of these global ambitions which led to massive changes in British society with the arrival of non-white faces in the UK in significant numbers for the first time.

During the slave trade in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, slave owners brought some of the first Africans to Britain, although by 1770 this still only numbered some 14,000 in a population of around six million.

Then during the First World War thousands of men from across the Empire fought for Britain, with some staying behind to live afterwards. But it was the end of the Second World War, and the decision of the British government to address labour shortages by opening up migration from the fast shrinking empire, that would have the most fundamental impact on the ethnic makeup of the UK.

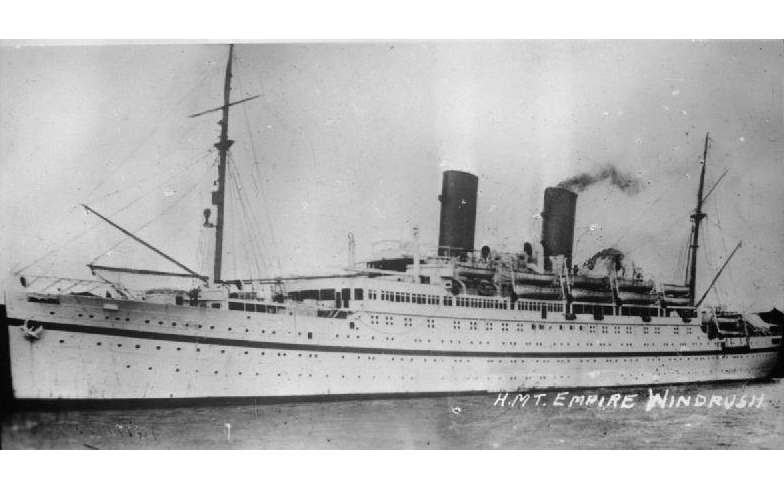

On 22 June 1948, the Empire Windrush ship docked at Tilbury in London; the thousands of men and women from the West Indies who followed after became known as the Windrush generation. Around the same time, immigration was also taking place from South Asia with migrants arriving during the breakup of the empire and the independence of Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka, and later Bangladesh. In 1945, Britain’s non-white population was in the low thousands. By 1970 it was 1.4 million – a third of these were children born in the UK.

The mass immigration of people from the Empire – who had fought for Britain during the war and carried British passports – was met with a rise in racial violence and prejudice from the white community. Under pressure, the government moved to make it harder for non-white people to arrive in the UK, so by the 1970s immigration had fallen drastically.

In 1972, however, the Ugandan dictator General Idi Amin expelled 80,000 African Asians from the country, many who held British passports from the empire days, and during this crisis 28,000 arrived in the UK in just two months.

This first generation of immigrants arrived in the UK during a time of huge social upheaval – especially as it related to gender and sexuality. Male homosexual sex was decriminalised in 1967, women were living lives independently from men, and from the 1970s onwards there was a huge increase in the numbers of social groups formed specifically for gay and lesbian people.

This was followed in the 1980s with the first gay clubs and bars – forming a visible and permanent subculture in Britain. But just because these LGBTQ people shared a common history of persecution and discrimination, it did not necessarily translate that they would share an understanding of the similar prejudice experienced by non-white people.

The gay scene in Britain in the 1970s and 1980s was dominated by white men. For women, this meant being treated by the same sexist standards that heterosexual men traded in, including assumptions about domestic work in LGTBQ groups, and even whether they should be included at all.

Women responded by leaving the Gay Liberation Front, forming their own groups, and in many cases prioritising their gender over their sexuality in the fight for equality.

Lesbian feminism emerged as a political response, which focused less on same-sex attraction, and more on female unity in defeating sexism. This was particularly the case as gay women were not subject to legal discrimination in the same way as gay men.

For BAME people arriving in the UK for the first time, racism was an unexpected danger from a country they had been taught to revere and which had offered them a home and employment.

While the UK appeared incredibly liberal in comparison to the socially conservative and religious communities they came from, LGBTQ migrants still faced the same racism in the gay community. Some describe being sexualised by their ethnicity – in many cases seen as a prize to be won – or else ignored in favour of the hegemonic image of the white masculine clone.

Others faced outright discrimination, barred from entry to clubs and bars or else accepted into LGBTQ groups as an exotic ‘other’, only to find themselves excluded when they began to assert their own ideas and politics. As with lesbian feminism, this led to a debate about whether to claim a gay or a BAME identity.

In many cases they chose to work with BAME activists and raise issues of sexuality, rather than raising racism in gay activist circles.

Many gay BAME people felt that along with a perceived obligation to normalise their sexuality for the heterosexual majority, they were also being asked to normalise their race and dilute their culture; when taken together this represented a full-on assault on their whole identity.

If you were a gay BAME woman, moreover, you would also have had to endure the pernicious effects of sexism – a third intersection of identity. Groups such as the Long Yang Club and the Gay Black Group emerged to challenge this assumption, and reassert both culture and

sexuality.

While we would now distinguish between the experiences of Black and Asian people, many Asian men and women defined themselves as Black during this period in a shared experience as outsiders in a white-dominated LGBTQ community. This included a lack of cultural awareness, full appreciation of the effects of racism, or understanding of what it meant to be gay and Black.

These groups were the first opportunity for BAME people to make sense of sexuality and ethnicity on their own terms, as well as avoid the inherent racism of much of the gay community, and indeed homophobia of their own ethnic communities.

This was especially the case for the second generation of migrants – the sons and daughters of those who had arrived in the UK who had a unique experience of being both Black and born in Britain. This involved negotiating ties with their heritage despite physical distance, while simultaneously maintaining a British identity, often in the face of white British hostility. Thus the groups helped members negotiate the tricky terrain of coming out to parents, having pride in their cultural and ethnic background, as well as finding other like minded people who fully comprehended the unique experience of being an ethnic and sexual minority.

Racism within the gay community still exists, as does homophobia within some BAME communities. It is therefore vitally important that we acknowledge the good and the bad of our shared history in order to fix these problems for the future.

It is also important to preserve the history of these communities’ experiences. The rukus! Black Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender Cultural Archive aims to collect archival material from the Black LGBTQ community – recognising the lack of Black gay history in the UK.

In addition, groups which cater for a specifically BAME LGBTQ audience, including the Naz project, and UK Black Pride – now supported by Stonewall in recognition of the alleged lack of diversity in Pride in London – help address the still present conflict at the intersection of sexuality, ethnicity, and gender. Black, Asian, and minority ethnic people have a unique experience of expressing their sexuality and sexual identity in the UK – something it is important that we all acknowledge.