I was recently giving a talk for LGBTQ+ History Month to secondary school pupils in my role as a volunteer ambassador with Just Like Us, the LGBTQ+ young people’s charity. At the end of the session, a pupil asked about my experience of homophobia at school. “I was very lucky,” I said brightly. “Most of my school experience was very positive.”

If I had had more time to answer the question, my answer would not have been quite as straightforward. It’s true that when I came out as a lesbian at 14, my friends and family were supportive. But I also worried constantly that my peers’ acceptance of my sexuality depended on it never being visible. Although I was thrilled to have become part of a community that was playful and creative in its exploration of gender norms and celebrated non-conformity, I was terrified to embrace that for myself. The fact that I dressed in a stereotypically feminine way seemed to make those around me more comfortable about my sexuality, so I stuck with it.

I didn’t tell anyone how much I admired butch women, especially the way they played with the boundaries of masculinity and femininity, refusing to conform. I envied the way they didn’t seem to care what anyone thought of who they were or how they behaved. I was awed by these women, but I didn’t allow myself to consider what it meant for my own relationship with masculinity. No matter how much I longed to cut all my hair off, ditch the dresses for three-piece suits and start a pocket square collection, it didn’t feel like an option. Presenting myself authentically meant that I would be putting a spotlight on my identity – it posed too much risk.

It wasn’t until I left school and moved to London for university that I began to experiment with my gender expression. I was tentative at first, but it became impossible to ignore the thrill I experienced every time I found something new that felt authentic. I discovered the joys of soft corduroy suits, flannel shirts, and a freshly broken-in pair of DMs. When I cut all my hair off a few months ago – eight years after I first came out – I couldn’t stop looking at myself in the mirror, amazed by how significant such a small act could be. It only took forty minutes in a barber’s chair to feel more like myself than ever before.

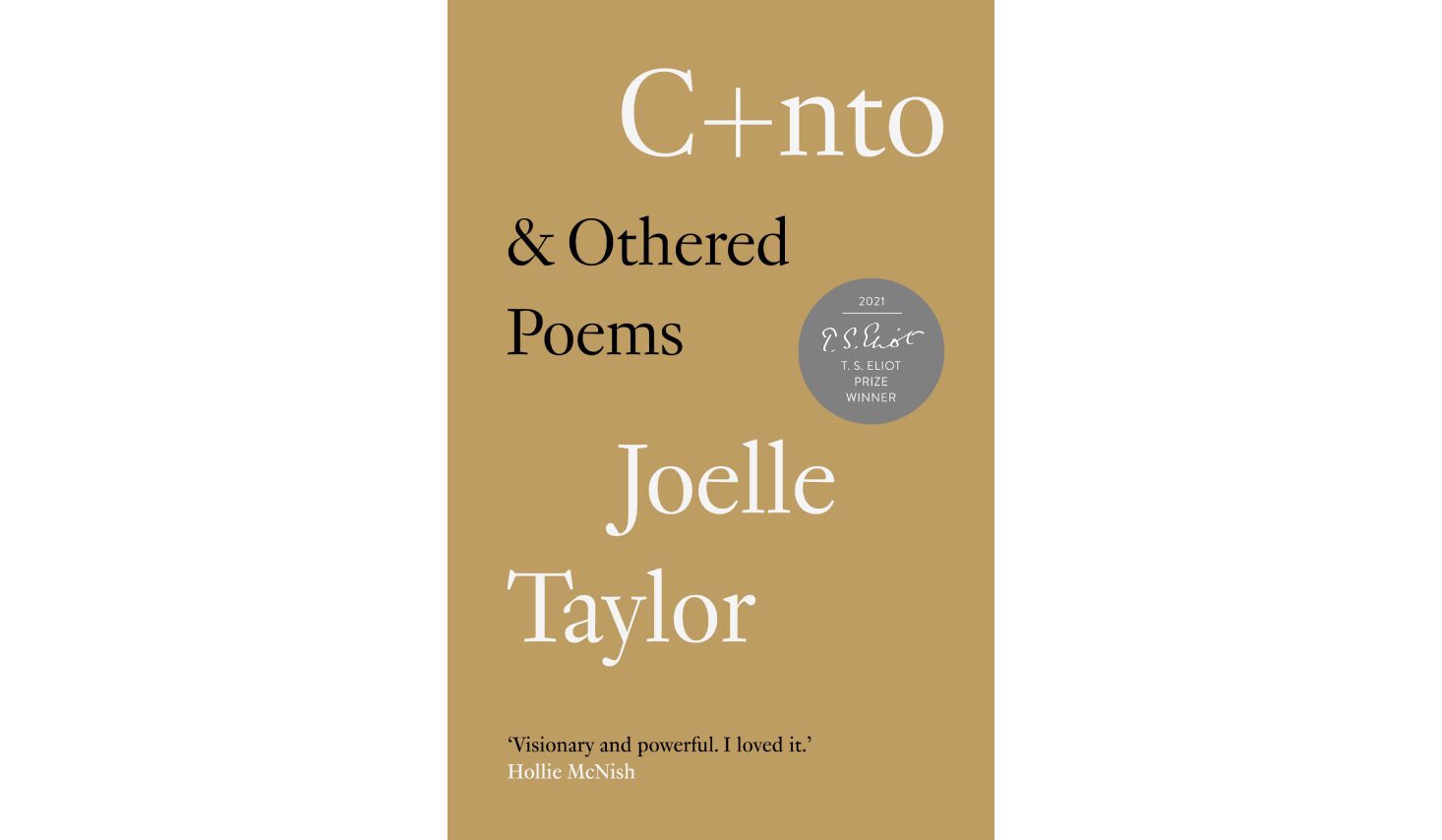

I have also discovered the joys of being able to celebrate other butch women openly. A few weeks ago, I was watching the poet Joelle Taylor perform extracts from her TS Eliot prize winning collection, C+nto & Othered Poems. Giving voice to the lives of butch women like herself, women who are so often pushed to the margins, Taylor commanded the stage. She embodied everything I wanted to be as a teenager but was too afraid to explore. Taylor was not apologising for who she was, nor asking for permission to take up space. She looked so free.

Without the visibility of women like Joelle Taylor, I would never have learned how to embrace my identity. The pressure I felt to conform as a teenager had a serious impact on my mental health, and the lack of LGBTQ+ representation – especially lesbian representation – made life even more difficult.

We know that LGBTQ+ young people are disproportionately affected by mental health struggles, and this is especially true for young lesbians. Just Like Us’ research has found that young lesbians were the most likely of any group to report feeling lonely since the pandemic began, with four in five (78%) reporting that their mental health had gotten worse during lockdown. This was the highest rate of any group polled, compared to 71% of gay boys and 76% of bisexual girls. The dual challenges of facing homophobia and sexism can make being a lesbian, and coming to terms with our butchness, very difficult. For me, these statistics paint a tough but very real picture, and hammer home the need for authentic representation to help LGBTQ+ young people feel less alone, as well as the need for better mental health support.

As I have discovered these new pieces of my identity, I have noticed a huge difference in how I walk through the world. I am more self-assured; I feel more empowered to take up space. I do, however, have the occasional wobble. I can sometimes sense my teenage-self panicking that I have become too visible. But my experiences volunteering for Just Like Us reminds me of how much I would lose if I suppressed that part of myself. Just before I gave my very first talk at a secondary school, I briefly panicked: would I alienate the students if I looked too butch? Should I soften my appearance somehow?

I needn’t have worried. As I talked about my experiences as a lesbian, the students were engaged, curious, and compassionate. I realised what a disservice it would have been to myself and the students I was talking to if I hadn’t shown up as my authentic self. When I give these talks, the message I want students to take away with them is that their identities, whether they are LGBTQ+ or not, deserve to be seen, valued, and celebrated. I have come to realise that that message only has power if I believe it for myself, as well.

To answer the question the student posed in that classroom: yes, I did experience homophobia at school. I wish that I hadn’t spent so much time hiding who I was, twisting myself into a shape that felt unnatural to appease those around me. And I must give thanks to those school pupils, a fresh haircut and Joelle Taylor, because I can now say with confidence that I have never felt more at home in my own skin.