What I find remarkable is how little we talk about the overwhelmingly queer history of India as it’s now known, but also in precolonial times when it was a land mass that covered a much larger area including what is now Pakistan, Bangladesh, Burma, Nepal and Afghanistan. The religious and cultural melting pot of Mughuls, Sufis, Hindus, Buddhists and later Sikhs were queer AF. From Rumi and his relationship with his teacher Shams to the gay Taj Mahal of Jamali-Kamali, not to mention the gender-bending deities and gods we worship – including one of my personal favourites Shikhandi, born a girl but raised a boy who became a warrior that won the great war in The Mahabharat.

Even today it is entirely normal for people of the same sex to hold hands, share a bed and engage in homosexual practices. It’s heterosexuality that is more readily policed with an emphasis on women maintaining their virginity until marriage. Hence all this sexual energy can be spent with friends of the same sex all under the radar within family homes and never discussed. And this is the point entirely; talking about it makes it a thing. Labelling it makes it a thing. Where fluidity of gender and sexuality is as much the norm as marrying and having children with someone of the opposite sex, then what is there to talk about?

This then begs the question: why are diaspora Asians, (and I’m going to refer to British Asians specifically here and even more specifically to the straight ones) so fucking basic when it comes to sex, let alone homosexuality in modern day Britain?

Okay yes, colonialism. Living in the birthplace of race and therefore racism is at best challenging for us people of the diaspora, so let’s for a moment focus on the great queer history of India and the turf I refer to above.

Up until September 2018, India had criminal legislation in place banning acts of homosexuality – yes, British legislation. But before the country was colonised, it was a land that was extremely sexually liberal. Needless to say the birthplace of the Kamasutra, but also the inextricably spiritual aspect of sex. Our visitors were aplenty from every part of the world, most commonly Europeans in the grips of strict rules, religious and eventually legal that restricted their ability to engage in anything other than sex that would lead to procreation. After all, the world’s wealth at that time lay in India. We could afford to be gay AF, because there is a direct correlation between thriving empires and their acceptance and even devotion to the queer. Whilst the dwindling West was desperate to grow its population and compete on a global scale (and many would argue still is), these European sex tourists would land on our shores and fixate on our free asses and join in while they could.

The missionaries, however, brought in the apparently optimal procreatory missionary position and alas, with the colonisation of our people, land and trade we were stripped and suffocated and buggered and left as the poster children of Oxfam ads.

What has lingered is the shame. The feeling that it’s our fault. That we deserved it and that we should be grateful for what we have. And little memory of the glorious and rich past of our ancestors.

I’ve been connecting with my ancestors more and they seem pretty gay to me. Much more than my brainwashed parents could wrap their minds around. So in honour of them, here’s a little more of our queer history and a reason why I think Asians are the gayest people in the world.

I mentioned Rumi who we all know and adore, but did you know that it was commonplace for Sufis to engage in homosexual relationships between teacher and student? And that the entire language of Sufi poetry and music is conducted in only male pronouns. The language of devotion to the beloved male Lord is spoken by the male Sufi, also directed to his male teacher. Religion, especially monotheistic religion is massively homoerotic, let’s face it.

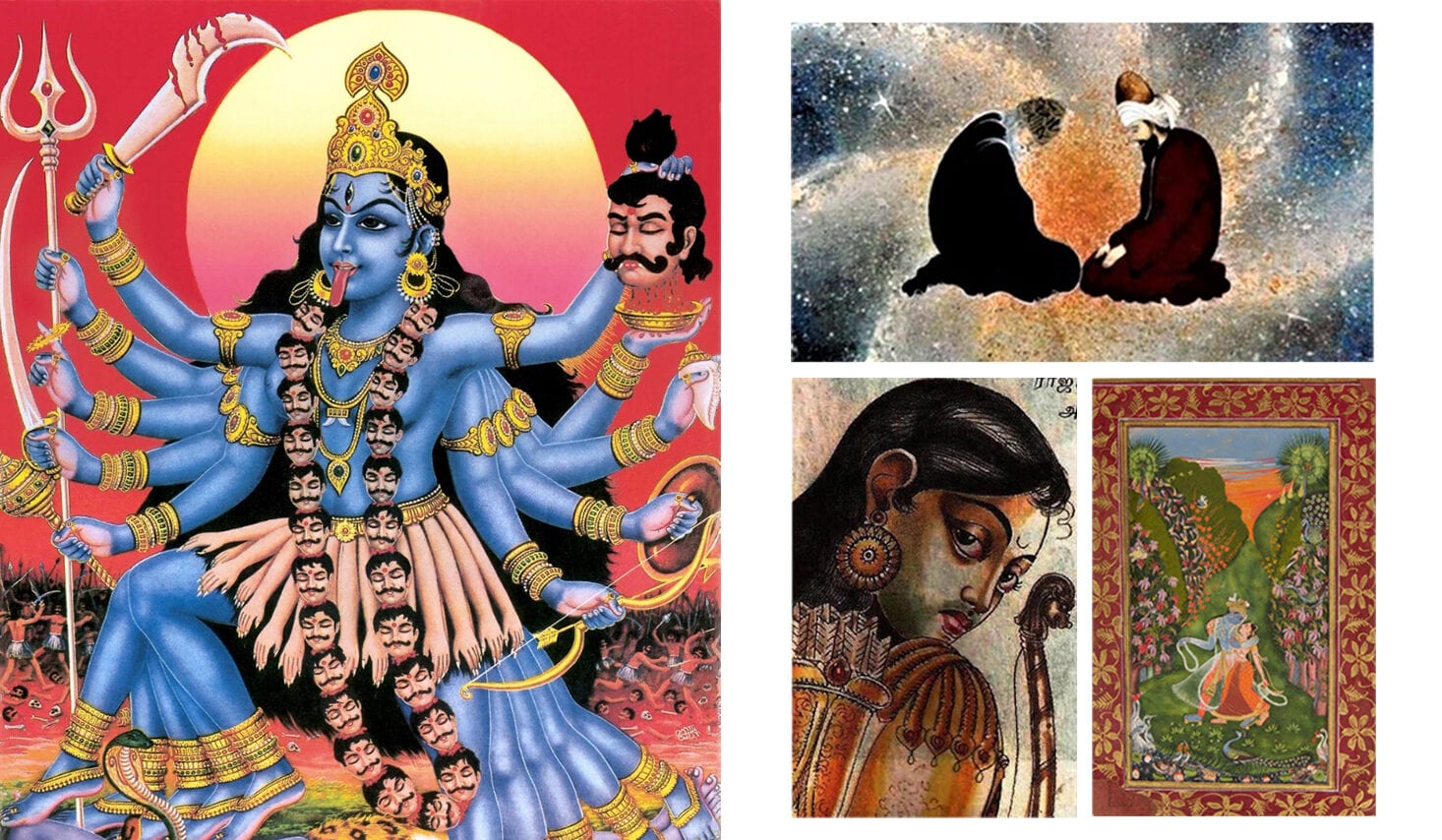

In Hinduism, the world’s oldest religion, scripture is bursting with homosexual and gender-queer and trans representation. Hindu gods and deities frequently change their gender and sexuality in the art of storytelling and fables and this is what many of us grow up learning. Then there’s the legendary Godess Kali, an absolute powerhouse and force of destruction, in fact our longest standing London LGBTQ+ Asian club night is even named after her. Kali actually hooked up with Shiva but then she became Krishna and started wooing milkmaids so Shiva became Radha to get her (now a him) back. Confused? It never seemed confusing hearing these tales as a child. A painting of Krishna as a woman, chirpsing the ladies, is in the Kota Place Museum and dates back to the 18th to 19th centuries AD. Krishna is referred to as purna-purusha or the ‘complete man’ embracing the divine feminine and the divine masculine in order to embody the divine whole.

Bhagiratha was a celebrated king and was actually born of two vulvas. The OG ‘kid with two mums’. Chandra and Mala were the two wives of the king and when he died, they fell in love and it is said that their union was blessed by Kama, the god of love and desire and Mala became pregnant with Bhagiratha.

The Kamasutra itself is named after Kama the god of desire who actually lost his limbs and hence personified the spiritual and energetic aspect of desire and sex. Vatsyayana’s Kamasutra, simply the most indepth text about sex in human history, has no fear or qualms in its rather practical inclusion of homosexuality, for it was never labelled enough to be othered. Interesting side note, the Kamasutra classifies anal sex as the exploit of sex between a man and a woman, not two men.

Overall though, ours is a culture of oral storytelling so we have few archives of our queer history now. Texts have been re and misinterpreted by the writers of our history. Not to mention the destruction and defacing of our gay statues to make them seem, well, not gay.

India’s intensely heteropatriarchal gaze wasn’t always what it is today. The right wing’s oppressive stronghold over the country which we see played out in the insidious oppression of the caste system – and now what has been building for years and bitten back in the form of the Farmer’s Protests – makes it hard for us to fathom the beauty of what was once a free and liberal land. The Khajaraho temples house a statue of a ‘yogini mela’ in the form of four women in a highly impressive sexual act from the 11th to 12th centuries AD. The Rajarani temple in Orissa is home to a stunning statue from the 10th to 11th centuries AD of oral sex between two women. But these statues of women and deities have been destroyed and defaced for decades, as have those of any acts deemed to be homosexual. I find this utterly heart-breaking.

In a country with 122 languages and 1600 variations of these, there is still no word for ‘lesbian’. But all this tells us is that language itself is a patriarchal construct and one that does the breadth of human experience a grave injustice. Whilst reconstructing language, it’s important to acknowledge that while language is important, it can never do justice to the human experience and it is merely one form of communication. I would go as far as to say that communication for women can be and is by nature, largely non-verbal.

Whilst Hinduism is thousands of years old and full of queer, same-sex and trans stories, a more modern religion in India is Sikhism (15th C) which barely refers to homosexuality at all and instead emphasises the equality and oneness of all. Again, language does not acknowledge something that perhaps requires no words and least of all judgement.

What the sacred Jamali-Kamali or gay Taj Mahal tells us is that two men can be buried next to each other in a manner that is normal for a husband and wife, in what is a spiritual home. And furthermore that the flat roofed dargah is traditionally a tomb for women only. That these two men loved each other and lived their lives together and were respected enough in death to be buried together, is achingly beautiful. Not to mention the more than symbolic female dargah in which they are buried together some 500 years ago and are to this day.

Sources and further reading:

Madhavi Menon’s ‘Infinite Variety. A History of Desire in India’

Devdutt Pattanaik’s ‘I am Divine, So Are You’

Giti Thadani’s ‘Sakhiyani. Lesbian Desire in Ancient & Modern India’

Gaysi Family’s ‘For The Love of God’