More often than not, queer spaces exist because of queer Black activists, but many of these spaces no longer feel inclusive of Black people. As a Black, gay man, my feelings are complex in this regard. Too many young Black men have been turned away from certain queer clubs, and as much as I want to include myself and belong to spaces that are meant for queer people, I’m beginning to feel uncomfortable in the fact that other Black men, who often have darker skin than my own, are being pushed out of them.

To be clear, I feel very lucky to be both Black and queer. Found deep within both, particularly Blackness, is a culture that gives me so much life and such a feeling of affirmation. As an example, I used to be insecure about having Black features, such as my nose when I was younger but growing up and seeing both family members and others be confident about their Black features made me feel so happy in my own.

Black History Month is a way to reflect on the joys of being Black – and I will – but, in this, I can’t turn a blind eye to the racism that is found within the queer community, whether it’s in clubs, on dating apps or over social media. Those in charge of these spaces seem disinterested in protecting the Black people within them, but it is notable that the jobs that they are in and the money that they are making from being in charge would not exist without Black activists such as Ted Brown, who helped to organise the UK’s first official Gay Pride.

Admittedly, I value my Blackness over my queerness – a homophobic person would not necessarily recognise me as outwardly queer, which is a privilege that I have alongside being light-skinned. In this regard, I am less affected by the infrastructure that is built so solidly against Black people than I would be if I was dark-skinned.

In contrast, though, I am not white-passing or presenting, meaning that racist people can – and have – still recognise me as their opposite. Before anything else, I am a Black man, and with this comes pressure to ensure that this aspect of my identity is respected within the queer spaces that I should belong to.

Research by Just Like Us, the LGBTQ+ young people’s charity, found that Black LGBTQ+ pupils feel more unsafe in school than white LGBTQ+ pupils – this is unacceptable as it is, but more so that it is also reflected beyond school and in spaces that are meant to be inclusive.

Thankfully, there are other spaces that have been created specifically for queer Black people to express ourselves within, such as UK Black Pride, and we can seek out our own spaces, too.

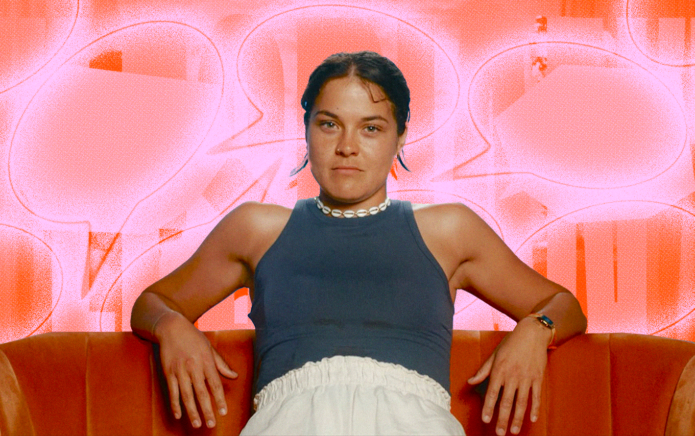

I feel able to express myself through my work, my training as an athlete and through volunteering for Just Like Us, where I am able to speak to young people in schools about my sexuality and other LGBTQ+ identities. Considering the findings of their research, I feel lucky to be able represent an openly Black, gay man while speaking to young people, particularly Black LGBTQ+ pupils who may not feel represented in their schools.

It’s upsetting that anybody should feel unincluded in someone else’s version of inclusivity, and queer people need to use October (and beyond) to go deeper into learning about queer Black history and the people who led us to where we are now. Every young, Black man that is turned away from a queer club pushes me further away from these spaces, but the more that Black people feel pushed out, the more we will seek out other spaces to express ourselves within – in my eyes, it’s clear that this does not reflect those being pushed out, but the spaces themselves.

For more information about Just Like Us and their incredible work supporting LGBTQ+ youth, visit their website.