Jobriath. Flash back to the ‘70s and the name was synonymous with flamboyance and embarrassment, an eccentric and talented glam-rock star who was hyped by the media and his management as America’s answer to David Bowie, a move that proved fatal to his career before it had even taken off.

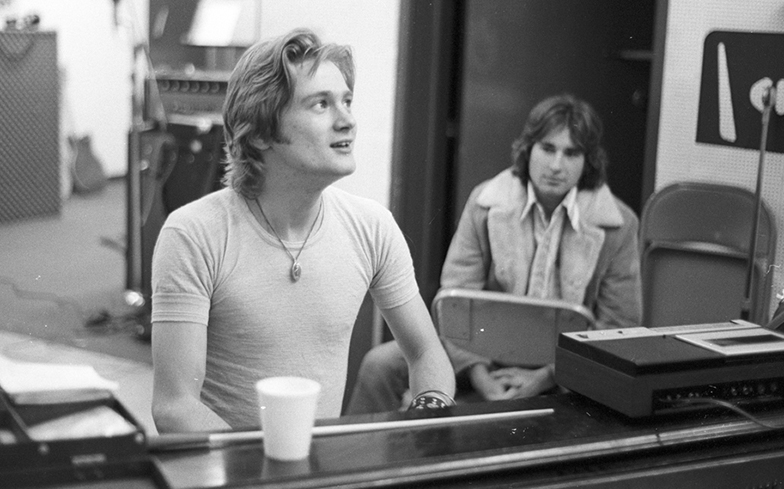

After landing a role in the musical production Hair, and a short stint as the lead of a folk-rock band Pidgeon, Bruce Campbell, as he was named at birth, debuted under the new moniker of Jobriath in 1973 with a daring self-titled album.

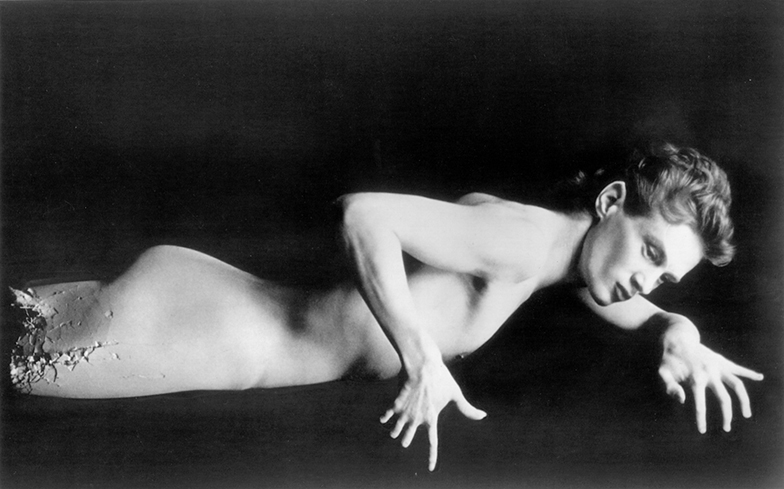

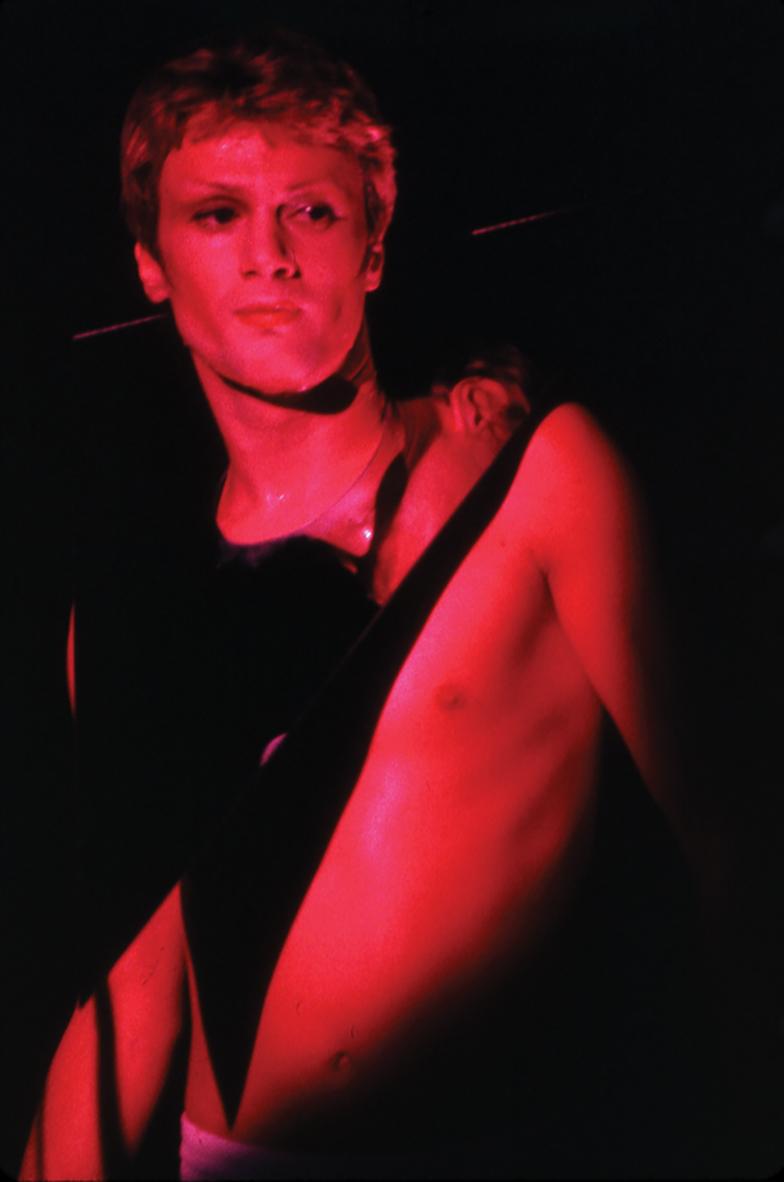

Jobriath’s theatrical music and androgynous imagery, coupled with his unapologetic attitude towards his homosexuality, was thrust upon the faces of an unsuspecting American public with an unprecedented amount of publicity. Amidst billboard advertisements and fabulous costumes, the should’ve-been-prodigy fell victim to the ruthless press and the public’s predominantly conservative views, before his untimely death as a result of AIDS-related complications.

Jobriath was the world’s first openly gay musician to be signed to a major record label. While fellow glam rockers like David Bowie played up to queer sensibilities, he was the real deal, declaring himself “the true fairy of rock and roll” in front of a world that simply wasn’t ready to accept that. Straight audiences berated him – with NME referring to him as “the fag end of glam rock” – and gay men, who were in a period of leather and hyper-masculinity, refused to take ownership of his unapologetic flamboyance.

Now he’s all but been forgotten, save for a few individuals who are seeking to give him the recognition he deserved. One of the leading pioneers for the Jobriath revival is American writer and director Kieran Turner, whose documentary Jobriath A.D. seeks to raise awareness of the lost gay icon. But what inspired him to make a film about an artist so obscure and – until now – relatively unknown?

“I hadn’t really set out to make a documentary,” he confesses. “I like them, but I wasn’t interested in doing one. I’d always heard of Jobriath – as I love the 70s, music and LGBT history – but it was always in the context of a joke, or negatively. I’d never heard the music and the images, to me, looked silly, so I never really pursued it.”

He came across his music by chance, a decision on a whim that would lead to a newfound obsession, recalling: “Back in 2007, I was ordering something online and they recommended a CD which was a Jobriath compilation put out by Morrissey on his own label. I hadn’t thought of Jobriath in quite some time and decided to order the CD to hear just how terrible it was.

“To my great surprise, what I heard was beautiful, original, stirring and made with immense talent. I had to know why it failed and thus was the genesis of the whole project. I fell in love with telling this story.”

Ask the common man or woman and they would likely have no clue who Jobriath was or what he did. As a result, information is relatively scarce, save for a few online articles and remnants of old newspaper excerpts.

“The most difficult thing was tracking everyone down who did know him, for several reasons,” Kieran continues. “Jobriath wasn’t around for very long, so that made the people publicly present in his life limited. I only had a short list with which to start and wound up finding others through word of mouth.”

True to form, Jobriath’s constantly changing appearance and various personas made pinpointing information on him difficult.

“Jobriath was something of a chameleon,” Kieran says. “Every time he shed a persona or alias, he would shed everything that went along with it. That meant that every phase of his life had a brand new cast of characters. I would interview someone and they could only talk about a very specific time in his life, nothing more. So it meant I had to track down probably five times the amount of people one would normally seek out and interview for this sort of thing, and hope they could tell me something new. There was a lot of overlapping information and several people were left on the cutting room floor.”

A number of those interviewed for the documentary are famous for making music themselves. While Morrissey, who was responsible for a Jobriath CD compilation release in 2004, refused on several occasions to take part, names such as Jake Shears of The Scissor Sisters and pop hit-maker Justin Tranter share their stories of the influence his work had on them in the film.

“One of my early ideas was to talk to current out gay musicians to see how things had progressed in the then 35 years since Jobriath had debuted,” Kieran explains. “I was very nervous I wouldn’t have enough material for the film, so I tried to take the scope of the story further than just the life of Jobriath. As it turned out, I had too much material, and I could only use those musicians to speak specifically about Jobriath. Thankfully, all of them knew of him, were fans, and could really talk about it.”

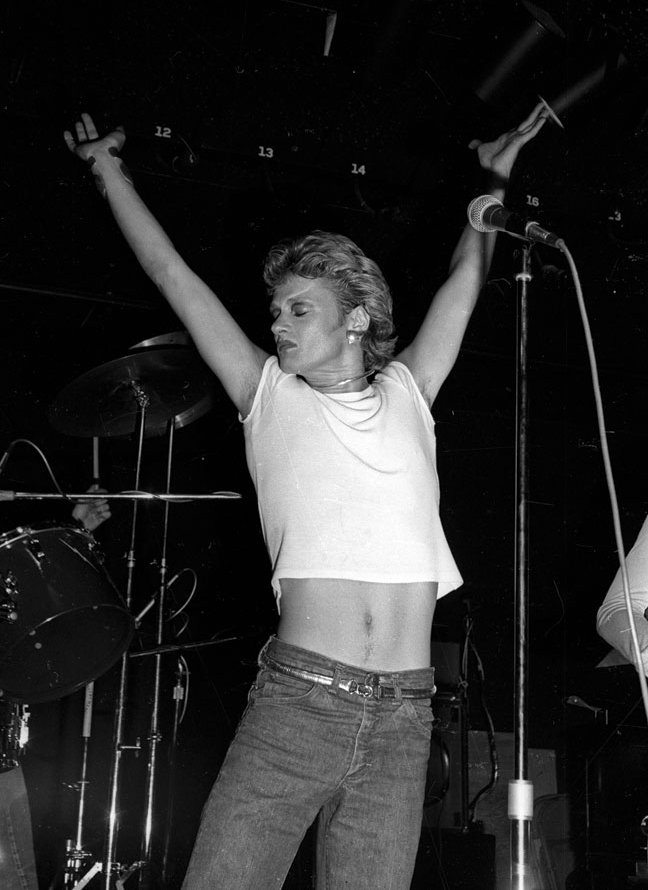

The scale of the hype that surrounded Jobriath ahead of his self-titled debut album, brainstormed and funded by his then-manager Jerry Brandt, was something unheard of at the time. Posters were brazenly displayed across buses and billboards were plastered with his face before the public had heard a single note of music, while Brandt compared his talent to superstars like Elvis Presley and The Beatles.

“People were not hyped like that back then, especially without having heard the music,” explains Kieran. “It was 180 degrees different from how it is today. Albums took months to break, music acts got two or three albums to try and see how they would fare with the public.”

A three-night live debut at the Paris Opera costing $200,000 was arranged, in which Jobriath planned to show off the true scale of his overtly queer creativity: He was to emerge dressed as King Kong on a mini Empire State Building, which would turn into a giant ejaculating penis as he transformed into Marlene Dietrich. Unsurprisingly, the shows never went ahead.

With all the excitement and calculated publicity, it’s easy to see that expectations were almost entirely unreachable; the quality of the music unfortunately did not matter. After live performances on The Midnight Special that left audiences viewing him as little more than a parody, and music that failed to reach even the top 100 charts, there was simply no money to be made. The commercial project that was Jobriath was deemed a failure.

“I don’t think you can point to just one factor and say ‘that did it’. It was a perfect storm of too much, too soon,” Kieran says. “Too gay, too much hype, too bizarre, non-commercial music, a label who wasn’t paying attention – it all contributed and it ruined him. He was simply ahead of his time.”

Following two unsuccessful albums, and holding the little that was left of his mainstream career, Jobriath announced his retirement from music and removed himself from the limelight, taking up residence in a glass pyramid above the Chelsea Hotel in New York, even going as far as changing his name.

“[His manager] Jerry swears up and down that he was not stopping Jobriath from using the name Jobriath, but I don’t think that’s true,” Kieran muses. “I think necessity was the mother of invention for Jobriath, but I also think it was in his nature and I think that he would have done it even if there were no legal issues with Brandt.”

Jobriath began performing cabaret in hotels and restaurants as Cole Berlin – a play on the names Cole Porter and Irving Berlin, both notable figures in the music industry that came before him.

“He could have continued calling himself Jobriath professionally, but he was done with glam rock, which I don’t think ever really fit him correctly and wasn’t really who he was. Cole Berlin was definitely more who he was.”

Tragically, Jobriath was one of the first famous musicians to fall victim to AIDS in America. He was aged just 36 at his time of passing in 1983, where he was found alone in his apartment days after his death. No one knows if he would have eventually found success, but it can be argued that his untimely demise has become part of his legacy.

“He had the potential to be Michael Feinstein had he not died,” Kieran argues, comparing his talent to the popular New York cabaret performer. “The issue with Jobriath is, I think, that he was scared of success. I think he was terrified of history repeating, so he locked himself up in the pyramid and he worked to keep himself solvent and because he loved the music, but I’m not sure the killer ambition was still there.

“Though it pains me to say so, I think it’s absolutely on the mark to say that his death was part of his legacy.”

Jobriath A.D. is available to purchase digitally on iTunes now.