Set in 1960s Britain before the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality in Britain, Peter Gill’s 2001 play The York Realist is playing at the Donmar Warehouse in a timely revival that coincides with LGBT History Month.

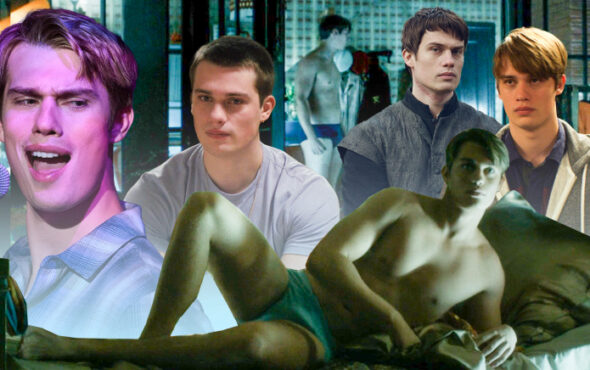

It’s about a closeted Yorkshire farmhand George and London assistant theatre director John, superbly played by Ben Batt and Jonathan ‘Jonny’ Bailey, who fall madly in love but find they’re from very different worlds.

Gay Times spoke to the two stars of ‘one of the most perfectly crafted gay love stories ever put on stage’.

Related: Talking About Jamie: LGBTQ theatre soars at 2018 WOS Awards

Does it feel especially poignant that the revival is on in LGBT History Month?

Jonny: Definitely and it’s all the more reason to come see the show because it gives what I think is a very human perspective. We afford ourselves now to examine and think about how we feel in relationships and the idea of compatibility. In gay stories that pre-date decriminalisation it’s more about the outside effect on the men and the sort of hatred that existed, but this comes from another angle. It’s genuinely about two people who, for a short portion of their relationship, are stripped of the obstacles to being gay because they’re in a farmhouse in Yorkshire and you see them falling in love for who they are. I think LGBT history should always be humanised as much as possible.

How would you sum up your contrasting characters in the show?

Ben: George is a lonely, suppressed guy who feels he can’t be honest with anybody about his sexuality, especially since the story is set in the 1960s before the 1967 decriminalisation act. So when he meets John it opens up these overwhelming feelings of love and excitement, danger and passion because now there’s a guy who totally gets him.

George seems more comfortable with his sexuality…

Jonny: What’s interesting about George is that he’s not defined by a societal appreciation of what it is to be gay whereas John has excited in a more progressive community in London so he’s questioned who he is more than George has and therefore he’s more cerebral and academically aware of the struggles of being gay. I think that’s why John is so attracted to and taken aback by George, who is inherently himself and has never had to question things. John tends to overthink things and probably has more anxiety about the present.

Ben: Having spoken to Peter Gill, he said George isn’t a man who would have lost a single night’s sleep thinking or fretting about his sexuality. That’s who he is and that’s what he wants from life. He’s incredibly comfortable being gay and because he’s in Yorkshire, rather than in the cosmopolitan buzz of London, he won’t have encountered other gay men who are willing to speak about it. He doesn’t have to explain himself to anybody, he just gets on with it.

Related: Beach Rats is a gay movie that dared to be real – here’s why it deserved more

From researching the time period, what have you learned about the problems faced by gay men in the early 60s?

Jonny: I spoke to Peter Gill and some of his contemporaries who at the time would have been working, as John is, at The Royal Court which was sort of a haven for gay creatives. They did not even acknowledge their sexuality to each other at the time. I spoke to one very famous theatre director who said it was draconian, like double leprosy, the idea of being gay. I worked with Ian McKellen just before Christmas doing King Lear in Chichester, where the National Theatre was founded and where he worked back then. He told me there was no real acknowledgement of sexuality between even the closest of creatives, even though they were ring-fenced in what was a very safe environment. In the run up to decriminalisation in 1967 it really was a very lonely time and impossible to live out a healthy and confident life.

Ben: Like the Civil Rights Movement in America you know what went on, but it’s only when you read about it in depth and speak to people who were around then, like our director Robert Hastie, that you realise how horrendous it must have been having people make you feel that how you are is wrong. I found that really hard to understand, that you couldn’t love who you wanted to love and feel able to express that freely.

The play is set five decades ago but how does it speak to contemporary audiences?

Jonny: It’s a gay play in that it explores a gay relationship, but beyond that it’s got a far richer depth in family and how your identity has to do with where you’re brought up. That’s a conversation we’ve had for years and it’s particularly loud at the moment in terms of how you can live in the same country and effectively have a cultural experience so far removed from someone else.

Ben: I’m going to steal something Robert said, which is that there’s never a bad time to put on a great play. And this really is a great play. It has a beautiful simplicity and without sounding cheesy I think it’s as relevant as Romeo & Juliet because it’s about what it feels like to be in love and how it feels to have that despair when you just cannot see a way to make it work.

Related: Love, Simon, 120 BPM and The Happy Prince among gay films to play at BFI Flare

Let’s be honest Ben, you look amazing when you take your shirt off but it’s not for titillation, is it?

Ben: No it’s not. I wanted to empathise George’s groundedness and physical strength to make it even more glaring how emotionally sensitive and vulnerable he is when John completely flips his world upside down. And any excuse to get in shape is a good one because I love beer and pizza and spend all my time when I’m not working gorging on things I shouldn’t be.

More information can be found here.