Shamir says 2020 has been a “bittersweet” year for him as an artist – one of the most surprising and exciting artists we have. He’s released two albums: Cataclysm, an intimate indie-rock collection which dropped in March, and this month’s brilliant, genre-blurring Shamir, which he describes as his “most accessible” since his 2015 debut Ratchet. “Honestly, it’s been all good for me career-wise,” he says on the phone from his home in Philadelphia. “But shit, every other aspect, like everyone else…” He pauses because at this point, no one needs another recap of why 2020 has felt like an endurance test. “And in some ways,” he continues, “that feels worse because I can’t really celebrate or set aside time to enjoy the fruits of my labours. It’s not like I can go anywhere, anyway, and why would I celebrate when so many other things are happening?”

Shamir Bailey – to use his full name – thinks his career has weathered a year where he can’t tour or promote his music in person because he was the only artist on his level “who was this equipped to deal with the times”. Because he’s “such a D.I.Y. artist”, there were “no logistical obstacles” stopping him from dropping songs as and when he liked. This D.I.Y. approach is definitely by design: when he broke through with the zingy house single On the Regular in 2014, Shamir was signed to British indie label XL Recordings, home to Adele and Frank Ocean. The following year, he released Ratchet, a well-received electro-dance album which he now describes as a “collaboration” because it mainly represents the musical vision of its producer, Nick Sylvester. Shamir and XL Recordings parted ways before he shared his transformative second album, 2017’s Hope, a musical volte-face which saw him ditch disco for lo-fi indie-rock.

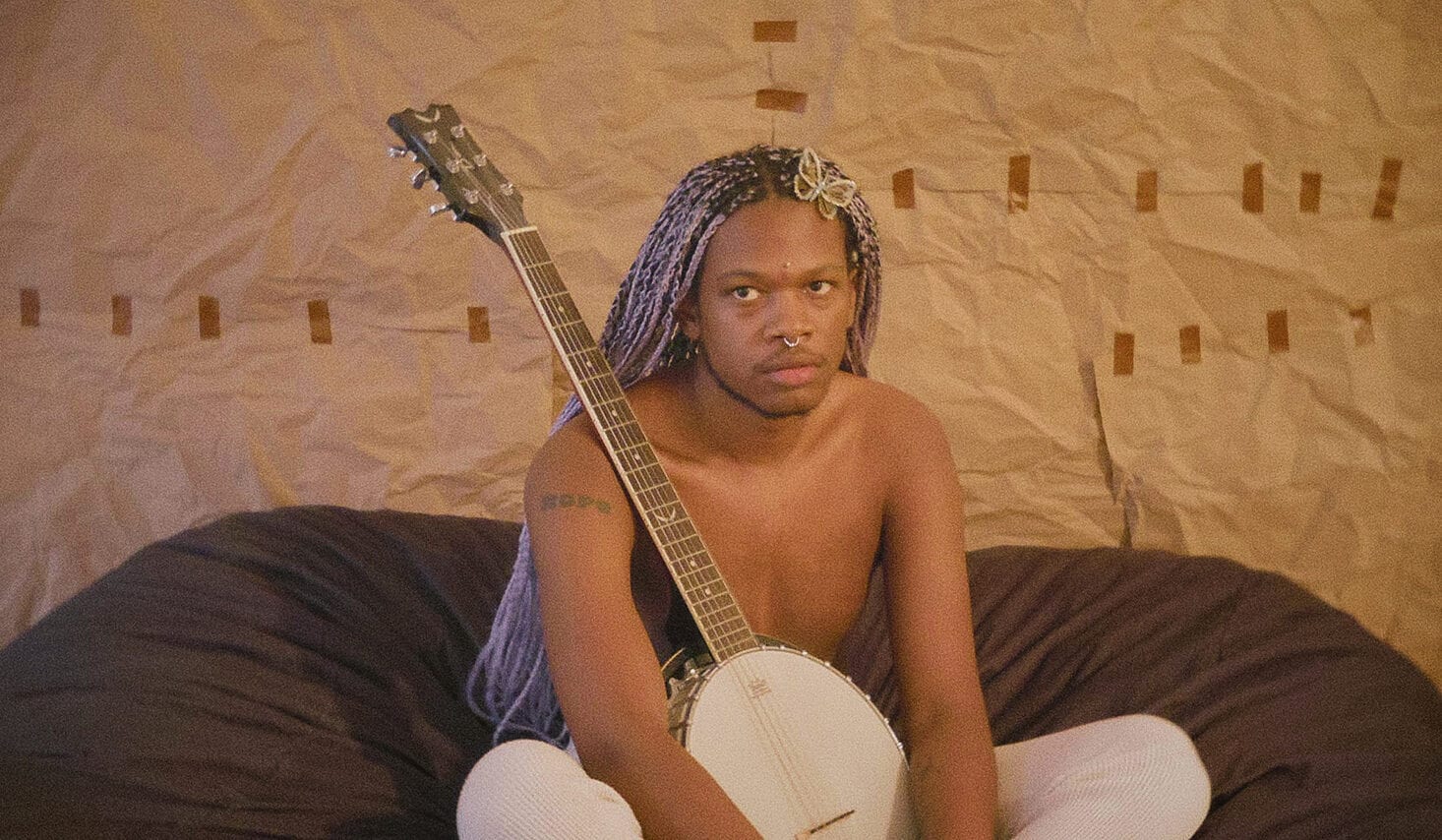

Shortly after Hope came out, Shamir experienced a psychotic episode which led to a five-day stay in a psychiatric hospital and his eventual diagnosis with bipolar disorder. Today, he says his mental health is “good – despite everything that’s going on”, and credits a more “mindful” attitude which has seen him cut back on alcohol and cigarettes. He’s clearly comfortable with the kind of musician he’s bloomed into. Having embraced the idea that he’s a role model for other non-binary folks – back in 2015, Shamir’s gender indentity was picked apart ignorantly in the media – he’s found his groove as a fully independent artist.

“For me, it’s definitely a case of the more people, the harder,” 25-year-old Shamir says today. “At a label, there’s just so many people to deal with all the time, so many tasks and so much filtering of ideas. But now, all of that comes from within me, which makes it so much easier to adapt and also make it fun.” He thinks his uncontrived approach to sharing music chimes with these uncertain Covid times. “Things that are too industry-ish and too business-ish don’t work right now,” he says. “Everyone’s kind of done with the overly capitalistic nature of things. Whereas someone like me who just goes where the wind takes them, that’s more humanistic first and foremost, and I think people relate to that.”

Shamir prides himself on staying authentic, but this doesn’t mean he’s slapdash or anti-strategy. Far from it: he says he spent a year working on his new, self-titled album to make sure it was “perfectly crafted” and captured all facets of his musical identity. To this end, Shamir is bookended by the shimmering indie-pop of lead single On My Own and a soulful orchestral closer, In This Hole. In between, he flexes from bracing grunge (Paranoia) to galloping country (Other Side) and wide-eyed rock balladry (I Wonder). When Shamir speaks passionately about his “rough trinity” of formative influences – Taylor Swift, Nina Simone and Tegan and Sara – his unique musical style makes a lot of sense.

Shamir says he laboured over the album because he wanted it to be his most “accessible and pop-leaning” yet. “And that’s because I felt such a real, substantial divide in my fanbase,” he explains. “There were pop Shamir people who liked Ratchet, and then there were rock and indie Shamir people, some of whom didn’t even know about Ratchet. And with this album, I really wanted to merge the two.” When Shamir first left electro-dance music behind, he says he was “bullied” by some fans who didn’t like his new, rockier direction. “Some of them were really ruthless,” he adds with a sigh. Shamir definitely hasn’t pivoted back to disco – the album is almost entirely guitar-based – but for the first time since Ratchet, he’s recruited outside producers to make everything as “squeaky clean” as possible.

Shamir reconciles his past and present to such an extent that Pretty When I’m Sad, a standout track, includes a lyrical nod to On the Regular – a song he recently admitted has “never been my favourite”. When he sings, “You can never see a queen without her crown, but sometimes it’s put up on her mantle,” it’s a throwback to On the Regular’s tough-talking couplet: “Step to me and you will be handled – see, that’s my crown on the mantle.” He says he included this reference to highlight “the trauma I felt around my first record when I felt like I had to be seen with a crown all the time, even though behind-the-scenes I was constantly crumbling”.

When I ask Shamir if it’s taken him time to feel comfortable showing a more vulnerable side, he gives an answer which reveals just how suffocating he found the Ratchet era. “No. And I think that was what was so frustrating about my initial success. Because I was on this fast track toward pop stardom, it felt like I wasn’t supposed to show my imperfections – I wasn’t supposed to be that open or candid,” he says. “And like, I constantly felt depressed. Because I love honesty – brutal honesty is like my kink. Any time someone’s brutally honest with me and I can be brutally honest back, that’s really the best thing for me.”

Five years after the Ratchet era, when he faced a stream of reductive interview questions such as “what does post-gender mean?”, Shamir can speak candidly about his evolving relationship with the non-binary label. “Back in the day, younger Shamir who was still crafting his understanding of being a non-binary person would say things like, ‘Labels don’t matter,’” he recalls. “But I know now that to a lot of people, they do matter. It’s not about getting rid of labels; it’s about everyone accepting everyone for who they are and just minding their own business. Right?”

Shamir gives an equally honest and nuanced response when I ask if “non-binary” fully encompasses his gender identity, or whether it’s just the best label out there. “I think that’s the case with any label, you know. I think ‘rock star’ is a good label for me, but is it really that accurate? And ‘pop star’ – is that really that accurate?” he says. “It’s the same with ‘non binary’: I think it’s just the closest thing for me. I’ve always been someone who lives outside of these margins, even down to the fact that I’m ambidextrous. I feel like I always live in this purgatory, it’s really insane! And I’ve had to really not think about it too hard.”

However, this doesn’t mean Shamir is in any way ambivalent about calling himself non-binary. “It’s the closest thing for me, but I say it proudly: I love my non binary identity,” he says, adding that he’s fully embraced the idea of being a role mode for other non-binary folksl. “I didn’t feel like one at the beginning because I was just so young and didn’t realise how politicised my identity was,” he says. “I mean, I had a clue, but I had no idea of the depth of it until I became an adult and was out in the world in a very public way.”

In fact, Shamir says he recognises the importance of his visibility more than ever because in the music industry, he’s still essentially in a category of one. “I was really just so frustrated after my Ratchet era, and after I decided to step back [from the industry] for a second, that I didn’t see my influence as much as I wanted to,” he says. “Like, I wanted to see more Black and non-binary artists – and that’s not to say they weren’t there – but, like, Black and non-binary artists being given the same platform I was given. And because they weren’t, it made me realise: ‘Yeah, my work is not done.’ I have to be the one to take up as much space as possible because I’m lucky enough to still have this platform and still have people be interested in what I do.”

Shamir takes an equally realistic view when it comes to the increased visibility of the Black Lives Matter movement following the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and other Black Americans killed by police. Four months after Instagram was filled with black squares, he says with a sigh that “I think it’s constantly been proven that this was largely performative”. Though he acknowledges that even performative activism has benefits, he adds bluntly and poignantly: “We’re having this interview the day after it was ruled that no one is being charged for the death of Breonna Taylor. Yeah, the performative activism can do those small things like inspire an individual to become more engaged. But when there are still so many systematic things [in place] that affect everyone, it makes you really not care to give the people who are performing a pat on the back. I feel like that [basic] level of activism should, like, just be required. It’s like going to school – if you go to school, you do your homework. You should be doing it anyway.”

“I try not to be negative about the performative stuff,” he continues evenly, “but sometimes it feels like it’s just playing in our face when we need action”. I suggest that people – white people like me – need to engage fully with systemic racial oppression even if this means we sometimes get things wrong when we speak about it. “Exactly,” Shamir replies. “So many times I have said something ignorant and I’ve been called out and shown that it was wrong. And every single time, I’ve been glad to know [why]. Everything is a learning experience. No one’s asking you to be perfect. No one’s asking you to have all the answers. Be open, listen and do what you can. And know that doing what you can and doing the least are two very different things.”

Given the overwhelming trauma fuelling the Black Lives Matter movement and the way coronavirus has decimated everyday life and his industry in particular, it’s no wonder Shamir considers this year “bittersweet”. But after speaking to him for an hour, it’s also clear that he’s in “a good place” and relishing life as an artist with seven years under his belt. Because of his unexpected career trajectory, I say that it almost feels like he should be older than 25. “Oh listen, I think about this all the time!” he replies. “There are grown people who come up to me and say, ‘Oh my God, I used to listen to Ratchet in middle school.’ And I’m like, ‘Wooooooo!’ But then you do the math and it makes sense. Sometimes I feel like I’m so old and haggard, but at the same time I fully understand that 25 is a very youthful age. And I definitely appreciate that it’s rare for an artist to have this resurgence after, like, half a decade.”

Rare, but in this case, entirely justified.

Shamir’s new self-titled album is available to stream and download now.