2018 was a great year for queer cinema. Call Me By Your Name was given the commendation it deserved after winning a BAFTA for Best Adapted Screenplay, and the highly-anticipated teen drama Love, Simon swept across cinema screens.

However, some LGBTQ films are being swept under the carpet. Why? Because they dare to show something we all avoid at some point in our lives: Reality.

I had never heard of Beach Rats until a friend recommended it. After I watched it, I was annoyed. Why wasn’t I already aware of this film? Why wasn’t it receiving the same rapturous response as Call Me By Your Name?

It soon dawned on me that perhaps the ugly truth doesn’t make for good cinema because we’re too used to seeing a resolved ending. It is now an expectation, and if it isn’t met, it is simply ignored.

Yes, films such as Call Me By Your Name don’t adhere to a fairytale equilibrium, but what they certainly do is provide us with a sense of closure – something Beach Rats dared to deprive us of.

And this is why it deserves recognition.

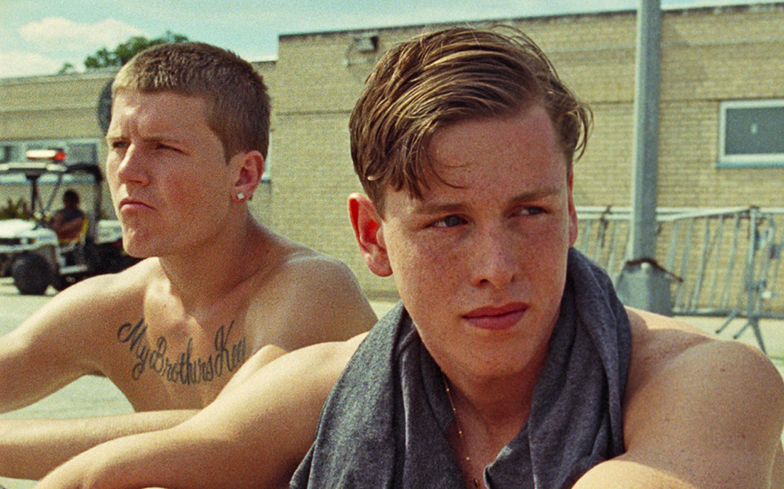

A ‘sad blue-eyed boy’ perplexed with his sexuality borders on cliche, yet somehow, Eliza Hittman’s production of Beach Rats is nothing less than painstakingly human and poignant. In a tale of tormented youth, protagonist Frankie, a Brooklyn teenager portrayed by Harris Dickinson, explores the dark side of gay culture as he finds escapism in the form of an online gay chat room.

Sat in his dark bedroom, and protected only by the cap he wears to anonymise himself, Frankie comes across his first online encounter, an older man who requests: “Turn on the light, I can’t see you.” He hesitates, because taking the cap off, turning the light on, or even uttering a single word could potentially expose him to a world he isn’t yet ready to admit he’s part of.

From this point, the character jumps irrationally between moments of spontaneous-hedonism and self-deprecation, depicting to the audience the shame he feels when admitting what he truly wants: “Don’t make me say it,” he pleads, as an elderly man stripteases for him on screen.

And this exposed feeling of shame is something that sadly resonates with many people within the queer community, rooted from the belief that our desires are immoral, perverted, and must be kept secret at all costs.

Frankie numbs himself through a concoction of drink and drugs, a dual coping mechanism used to help grieve over the death of his father. His maladaptive decisions are encouraged by his delinquent ‘friends’, who remain naively in-the-dark about his sexuality. He’s trapped in the mundane cycle of washed-up adolescence and expectations, and his pathetic fallacy of playing handball in the rain, by himself, highlights just how repetitive the days must seem to him.

Frankie’s relationship with men is always reduced to nothing more than a transient hook-up, never seeking more commitment than the confines of a one-night stand. So when he is served at the bar by one of his late-night experiments, he’s invaded by the threat that these two separate worlds may finally come face-to-face.

When I watched this scene I was uncomfortable, because I can clearly recall a time where I thought my sexuality had to be detached and hidden. The very idea that my sexuality, my night-time strolls and my darkest desires could one day collide with a world where I acted and behaved as I thought I should, was terrifying, and lured over my every move.

For Frankie, this isn’t nostalgia: It’s reality.

To compensate for the guilt he now feels, the confused teen makes an effort to seduce his ‘girlfriend’ Simone (Madeline Weinstein) but his attempt to enjoy sex with her is as staged as their relationship, based on the fear of suspicion for not pursuing such an attractive girl.

It’s clear that Frankie equates his sexual exploration with wrongdoings – as if his actions are sins that therefore need repenting – and after he runs crashing into the waves, he is washed clean from last night’s antics.

The viewer is constantly brought back to the visual of fireworks, and their connotations reflect Frankie’s emotions and behaviour. They’re dangerous, just like the toxicity of his friendship group and his dependency on alcohol and drugs. They go bang, just like Frankie does after he washes his ass and leaves his house. They’re loud and public, just like his relationship with Simone.

But perhaps the importance of fireworks is how quickly they burn out.

When fireworks do fade into nothingness, people walk away. Nobody stays around to watch the smoke camouflage its way into the background. This perfectly encapsulates the essence of Frankie’s encounters: There’s a spark, then it’s over. You either watch them bang, or they disappear into the unknown. As Frankie is told by one of his webcam hook-ups: “Not tomorrow, tonight.”

The film ends leaving many questions unanswered, because, as Frankie proclaims, “I don’t really know what I like”. The ugly truth is that battling with your own identity is often a perpetual fight, one which can only be fought internally and cannot be resolved with ‘the right guy’. Frankie’s conflict with himself feeds his frustration, and through trying to find who he is he’s left with whip-lash.

Queer films have fallen into the routine whereby there has to be a definitive resolution – the main character has to come out at the end, or find ever-lasting love, or gain self-acceptance.

It’s refreshing to be reminded that everybody’s journey isn’t so straightforward.

Some days you take three steps back, some days you run a marathon in the right direction. But those silent subway journeys reveal much more than any coming-out speech could. We’ve all rode them.

You can follow Liam on Twitter @LiamGilliver